Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

If the immediate adoption of comprehensive, carefully considered plans, and the unification of all important resources of relief can accomplish it, the Red Cross work in the flooded district of Ohio will mean rehabilitation at every stage rather than merely the distribution of supplies. This is the end toward which the efforts of Mr. Bicknell and his associates have been directed. The state and local authorities readily grasped the idea, and showed a real sympathy with its aim.

First of all, the Red Cross has itself received in direct contributions at Washington the sum of $1,750,000. Much the larger part of this was, of course, contributed with the appalling disaster at Dayton in view, though from the beginning it was recognized that there were serious needs elsewhere in Ohio, in Indiana and other states. The Ohio authorities received in contributions $611,632, and it was decided by the governor and the flood commission which he appointed, to expend this also through the Red Cross. Finally, the Dayton citizens’ relief committee, appointed by the governor and presided over by John H. Patterson, who had taken complete charge of the situation even while the river was overflowing the levees and inundating the town, has been receiving donations directly. It has been selected as the channel through which Red Cross funds available are to be disbursed.

While Edward T. Devine and Eugene T. Lies went to Dayton originally for the Washington Headquarters of the Red Cross, they also are doing their work under the authority and with appropriations from the local committee. They are assisted by Amelia N. Sears, secretary of Woman’s City Club, Chicago, who took part in the San Francisco rehabilitation work; Rose J. McHugh, secretary of Funds to Parents Committee, Chicago; Ada H. Rankin and Johanne Bojesen of the New York Charity Organization Society, who helped in the relief of the victims of the Triangle shirt waist fire and the Titanic disaster; Grace O. Edwards of the Chicago United Charities; Edna E. Hatfield, probation officer, Indiana Harbor, Ind.; Edith S. Reider, general secretary, Associated Charities, Evanston, Ill.; Helen Zegar of the Compulsory Education Department, Chicago, who was in special charge of the relief of Polish and other immigrant families at the time of the Cherry Mine disaster. These Red Cross agents are in turn aided by a corps of local citizens, especially principals and teachers in the public schools, members of spontaneously organized local committees, and others.

There is no longer talk of plans for rehabilitation, for rehabilitation is in actual process. The careful Red Cross registration which was begun before the end of the week in which the disaster occurred, is proceeding rapidly. Four thousand families had been registered and the supplementary visits largely completed at the end of two weeks. On the basis of this registration, furniture is being provided, assistance in repairing houses and cash donations of moderate amounts, and other measures taken. All of these are intended to be a distinct step, even if in some instances not a very long one, towards the restoration of ordinary family life.

Among the measures which have been adopted in the rehabilitation stage, as distinct from the emergent distribution of supplies, are the following:

Houses which were occupied by owners of limited means and which were comparatively slightly injured are being repaired by gangs of carpenters who work in one section of the city after another. The work mainly consists of putting frame houses on their foundations, moving them back across the street, or doing such other things as an owner unaided cannot do, but which a gang of half a dozen men, some of whom are skilled carpenters can do in half a day or a day. This service is not rendered if the owner is in position to hire men to do it, or if the house is so badly injured that it involves much labor and expense.

Owners of lots, whose houses have been entirely demolished, and who wish to rebuild on the same site, are to be given an army pyramidal tent equipped with cots and tent stove. These tents will be put up by a hospital corps, under the direction of an army surgeon who will advise where on the lot the tent should be pitched, see that sewer connection or latrine is in order, and give instructions as to the use and care of the tent, so that the investment of about $100 which the donation represents may not be wasted.

The greatest immediate need after food and 130dry clothing, is for furniture and mattresses to replenish the thousands of homes whose furniture is utterly demolished, or so badly wrecked as to be practically useless. The first impulse was to ship in large quantities of furniture and give it away, or sell it at cost. Fortunately, a live furniture man, the president, in fact, of the National Retail Furniture Dealers’ Association, was encountered accidentally early in the proceedings. He was asked whether the retail dealers of Dayton could not handle this matter themselves. One large furniture house was entirely destroyed, but twelve others remained. All were in the flooded district, but all proved to be uninjured above the first floor. On the first floor the more expensive kinds of furniture had usually been displayed. This was all gone, either bodily out of the window—these were the more fortunate—or in a hopeless mess of mud and wreckage in the building. The less expensive kinds of beds, tables, chairs and dressers were largely stored on the upper floors. It was, therefore, only a question of cleaning out the first floor—getting the elevators into operation—often a hard job in itself—and securing trucks or wagons for delivery. This was a still harder job, for those that were not gone in the flood had been impressed into military or relief service. But the retail dealers held a meeting of their association, and agreed to handle the problem, and later the department stores which carry furniture came into line. By resolution they bound themselves not to increase prices. Requisitions are therefore given after the Red Cross registration is completed, for from $10 to $100 worth of furniture, according to the losses and circumstances of the family, to be selected by the purchaser at any one of a dozen stores from a list printed on the back of the requisition. These orders are filled in the usual way by the dealer and already such goods are being delivered.

Transportation from Dayton and other points for women, children and disabled men has been given by the railways through to the real destination after the usual inquiries and precautions familiar to those who work under the national transportation agreement.

In the first few days refugees were carried free without question to points in the vicinity of Dayton, but on the opening of the Red Cross headquarters, this indiscriminate free travelling was at once replaced by the other system.

The first considerable issue of cash and furniture orders was made on April 9—about $10,000. Since that time the number of registered families ready for decision has been so great that it taxes the energy of the central office in spite of the excellent facilities at its disposal. In some instances these grants will have to be only first installments on account of a larger plan; in many others, and it is hoped the large majority, it will be all that is necessary. In each envelope with furniture order or check, Mr. Devine is inserting, over his signature, a printed slip as follows:

“The Dayton Citizens’ Relief Committee and the American Red Cross beg you to accept this expression of sympathy for your losses and hardships and their best wishes for the speedy restoration of your prosperity and accustomed manner of living.”

The date of the Third National Drainage Congress which convened in St. Louis April 10 to 12, seems almost to have been planned providentially. Just as significance attached to a similar meeting in New Orleans at the time of the Mississippi flood last year, the attention of this year’s gathering was concentrated on the problems which the floods of the central states have so insistently raised.

Important resolutions were passed in response to a suggestion from President Wilson that Congress should formulate some plan for the prevention of floods and their disastrous consequences. The resolutions were addressed to the President and Congress. They urged that the government, under the welfare clause of the constitution, should take adequate measures to control the water resources of the country, and continued:

“We respectfully petition the immediate consideration of adequate provisions for flood control, for the regulation and control of stream flow, and for the reclamation of swamp and overflow lands and arid lands, and in furtherance thereof we pray that in your wisdom you create a body which will put in effect at the earliest moment possible such plans, in co-operation with the several states and the other agencies, as will meet the needs of the several localities of the United States, and we believe the most effectual and direct means will be the establishment of a Department of Public Works with a secretary in charge thereof who shall be a member of the President’s cabinet.

“Be it further resolved that the wide scope of the problem of flood water control, affecting practically all the states of the Union, can best be conducted under the immediate supervision of the President of the United States in the exercise of such authority as is conferred upon him by the Congress of the United States.”

Control and prevention of malarial diseases were the subject of another important resolution. The prevalence of these diseases throughout the country, especially in regions frequently flooded, was declared to be a cause of “great disability, loss of earning capacity and a 131considerable number of preventable deaths.” Since there are well established methods of prevention, the Congress established a section on malaria with Dr. Oscar Dowling of the Louisiana State Board of Health as president and Dr. W. H. Deaderick of Little Rock, Ark., as secretary. It was resolved further:

“That the several states be requested to appoint malarial commissions and that the commission of the Southern Medical Association and other duly authorized malarial commissions be invited to join in this movement and that the co-operation of the federal government be requested through the United States Public Health Service and the Medical Departments of the army and navy.”

These efforts to combat malaria followed an important discussion of National Drainage and National Health by Dr. William A. Evans, formerly health commissioner of Chicago and now health editor of the Chicago Tribune. He pointed out that the aftermath from floods was frequently more serious than the disaster itself, and referred to the fact that in the flood of a year ago on the Wabash River there occurred 400 cases of typhoid fever at Peru, Ind., and 100 cases at Logansport, Ind. The main burden of his talk related to the fact that with the drainage of low lands malaria could be almost, if not entirely, extinguished. Malaria was declared to be the cause of more disturbance and economic loss than all the floods. It was estimated by Dr. Evans that the cost of malarial fever in the United States was $160,000,000 per year. The notable reduction in cases of malaria and deaths resulting therefrom in the Panama Canal Zone since the American occupation was vividly pictured as indicative of what scientific effort can accomplish.

Before its adjournment this month the Legislature in New Jersey finally passed a grist of bills in the field of social legislation. A large proportion, if not a majority, of these were pending when Woodrow Wilson left the state house at Trenton, and, as often happens, especially in the case of bills which carry appropriations, they came to a head during the last three weeks of the session. Mrs. Alexander reviews the notable part the governor-president had in their advancement.[1]

While no immediate steps were taken by the Legislature to relieve the congestion at the state insane hospitals, a movement toward a serious consideration of the whole subject of state care, custody and treatment of mental defectives, including the insane, the epileptic and the feeble-minded was inaugurated by a joint resolution providing $2,500 for a commission to report before March 1, 1914.

The Legislature decided to continue the Prison Labor Commission. In a general way the recommendations of this body were adopted. The Board of Prison Inspectors insisted upon retaining the powers of administration and control of the prisoners, leaving to the commission the power to plan and direct operations. The Prison Labor Commission is authorized to purchase a farm at an expense of $21,000. There is also $17,000 immediately available for stock, implements, buildings, fencing, fixtures and furniture for this farm. The general appropriation bill available next November provides $12,500 for the purchase of a quarry, $3,500 for the expenses of the commission, and $12,000 for buildings and furniture for the farm. The reformatory at Rahway has secured an appropriation of $5,000 for a foundry building. This is the beginning of a policy of trade school instruction. The output of the foundry is to be sold to state use account.

The appropriations for the other state institutions provide for a continuance of the research work going on in the several state institutions. The new reformatory for women at Clinton receives $25,000 for a new cottage, the Jamesburg School for Boys $20,000 for a trade school building, and the epileptic village at Skillman $55,000 to complete a custodial building and $110,000 for future building.

Besides these appropriation measures New Jersey has enacted a widows’ pension law, which will be reviewed in a later issue of THE SURVEY, a bill providing for summer agricultural schools, and a new parental school act which permits their creation under the educational authorities. Another measure which was passed is a new compulsory attendance law calculated to fill the gap between the educational authorities and those of the state labor department which went far to nullify the effectiveness of the old law. “Add to this program,” writes an enthusiastic New Jersey social worker, “a few odds and ends of laws and you can see Jersey is still hitting up the pace.”

At the call of the Council on Health and Public Instruction of the American Medical Association, forty-seven representatives of volunteer and philanthropic bodies interested in some special phase of the health situation in this country met on April 12 at the headquarters of the American Association for Labor Legislation in New York city.

Feeling that, with the multiplication of independent organizations, there is danger of overlapping of function, interference in work, duplication of effort and expense and lack of effective co-operation for want of a common program 132of procedure, the American Medical Association early in January addressed a letter to the executive officers of about thirty of the more important national organizations suggesting a conference to discuss a plan for co-operation. This proposal met with a ready response. Among the bodies that were represented at the meeting held in New York were the United States Public Health Service, the National Committee on Mental Hygiene, the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, the National Committee of One Hundred on Health, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, the Russell Sage Foundation, the National Child Labor Committee, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and the National Commission on Milk Standards. John M. Glenn, director of the Russell Sage Foundation was chosen chairman of the meeting and John B. Andrews, secretary of the American Association for Labor Legislation, who with Dr. Frederick H. Green of the American Medical Association had made many of the preliminary arrangements, acted as secretary.

Among the suggestions discussed by the representatives of the various agencies were the following:

1. A central national health organization, composed of one representative (perhaps the executive officer) from each of the fifty odd national health organizations in the United States.

2. An annual conference of this central organization in January at which might be discussed one topic of paramount importance in the health field, to the end that the work of the central organization during the year be centered instead of scattered.

3. Establishment of a central bureau or clearing house with an executive secretary and facilities for collecting and distributing information relating to the work of the various health organizations represented.

4. Provision of $10,000 to $20,000 for the expense of the central bureau.

5. Appointment of a committee (of seven perhaps) to study and carry forward the plans of the bureau of health organizations.

As a result of the discussion on these questions the following resolutions were adopted:

Resolved, that it is the sense of this meeting that we should organize as a conference, either independently of the American Public Health Association or as a section thereof or of any other organization which should later be decided, after investigation by a committee to be appointed to work out details.

Resolved, that a committee consisting of fifteen members, of which five shall constitute a quorum, shall be appointed by the chairman at his convenience, to report at a subsequent meeting.

That the private charitable societies of Boston oppose the plan to transfer to the state the care of deserving widows with dependent children as an independent class is indicated by the hearings on the various bills now before the Massachusetts Legislature. Four bills have been introduced at this session. The first of these (House Bill No. 815) provides:

“If the parent or parents of a dependent or neglected child are poor and unable to properly care for the said child, but are otherwise proper guardians, and it is for the welfare of such child to remain at home, the juvenile court, the probate court, or, except in Boston, any police, municipal or district court, may enter an order finding such facts and fixing the amount of money necessary to enable the parent or parents to properly care for such child, and thereupon it shall be the duty of the county commissioners, or, in Suffolk County, the city council of Boston, to pay to such parent or parents at such times and as such order may designate the money so specified for the care of such dependent or neglected child until the further order of the court.”

The second bill (House Bill No. 1369), which is even shorter, restates the general principles of the first bill without providing machinery for carrying its provisions into effect. It reads as follows:

“Children whose parents are unable to support them shall not be placed in state, county or municipal institutions, but if either parent, or any relative or other suitable person, is maintaining a home, payment shall be made to such parent or relative or other person for the support therein of such children.”

House Bill No. 1366, the third proposed act, was prepared by representatives of many of the principal charitable organizations of Boston.

The bill does not so much state a new doctrine of relief for dependents as define more clearly the duties of the local overseers of the poor and more definitely chart their course in their work preliminary to granting relief. The avowed purpose of the bill, in the language of its proponents, “is to correlate the various public and private agencies of the state into one co-operative relief system under the general control and direction of the state Board of Charities and to use the local overseers of the poor as the active disbursers of the relief granted.” It is also made the duty of the overseers to the first instance to determine whether the mother is “fit to bring up her children and that the other members of the household and the surroundings of the home are such as make for good character, and that aid is necessary.” If this question is decided by the overseers in favor of the applicant they then are charged with the further 133duty of investigating the financial resources of the family and relatives, although the law does not clearly state to what degree of consanguinity this inquiry shall extend. They shall next inquire as to “individuals, societies or agencies who may be interested therein.” If they have by good fortune found anyone who is legally bound to support the mother and child, they are directed to enforce the full legal liability of the obligation.

They are admonished to get the family to work if possible, and to secure such relief as can be obtained from organizations and individuals. The law adds, however, that none of these directions shall be construed “to prevent said overseers from giving prompt and suitable temporary aid pending compliance with the requirements of this section, when in their opinion such aid is necessary, and cannot be obtained from other sources.” The bill provides, therefore, that local overseers shall aid such mothers and children as they deem worthy if they can find no one else who can be forced or coaxed into doing it. The bill further provides that the overseers shall follow up their initial activity by visiting the recipients of aid at least once in three months and shall keep a careful detailed account of the conditions found at each visit as a part of their official records. It is made the duty of the State Board of Charity to supervise the work done by the overseers and to report thereon in its annual report to the state Legislature.

This bill was presented because of the report of the commission on the support of dependent minor children of widowed mothers, and the measure (House Bill No. 1770) proposed by the commission. The general court of 1912 created a commission to investigate the condition of widowed mothers, provided $1,000 for its expenses, and ordered it to report at the present session. The commission as appointed consisted of Robert F. Foerster of the department of social ethics of Harvard University; David F. Tilley of Boston, for many years a member of the Central Council of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and at present a member of the State Board of Charity, and Clara Cahill Park of Wollaston, Mass.

The report of the commission and the arguments in support of its bill in general were:

That the present system of outdoor relief is inadequate;

That frequent separation between the widowed mother and her children occurs;

That the cause of the mother’s dependence is seldom purely local but a matter in which the state in the large is concerned;

That therefore the state should grant the relief and not the locality alone;

That while all needy mothers, whether widowed or not, are proper subjects of the state’s bounty, yet widows are in a class which need a different technique of relief.

The commission expressed its belief that widows’ families were the most important single group in poverty and that they should be dealt with by a method unhampered by the need of dealing with other cases. The commission’s bill, it was argued, would further break up indiscriminate relief, introducing state control and state standards for a great group of dependents, continuing the process begun for the feeble-minded, insane, blind and the like. The friends of the bill believed that the state Board of Charity administered so much relief that widows would not be adequately cared for by it. They urged that while House Bill No. 1366 in terms disclaimed any intention of regarding its proposed relief, pauper aid, yet in fact it could not fail to be so regarded by possible claimants. The commission called the aid it proposed giving subsidies rather than pensions, as it regarded its aid as in no sense payments for services rendered but assistance in rendering needed service to the state.

The report of the commission was signed by Professor Foerster and Mrs. Park. Mr. Tilley presented a minority report stating that he was fully in accord with the desire of the commission to adequately assist widowed mothers with dependent children, but that he felt that the report was based upon insufficient evidence. He further believed that the present machinery of relief was entirely adequate for the purpose desired.

The bill proposed by the commission provided for a permanent commission of five, two of whom should be women, who should have authority to order subsidies paid by the overseers of the poor, in such sums and manner as the commission should decide. The commission is authorized by the bill to make its investigations by its special field agents, and it is made the duty of the overseers to visit the family at least once in every four months and to report its condition to the commission. Two-thirds of the amounts paid to families who have no settlement and one-third of the amounts paid to all other families shall be repaid to the overseers by the state Board of Charity. No relative other than those legally bound to aid the family, and no private society shall be asked to contribute any portion of the subsidy.

The commission by its bill provided a new state machine designed to administer a specific pension or subsidy to a specific class of dependents. The bill proposed by the opponents of the commission’s bill, defined and enlarged the present relief machinery of each locality. The purpose of the friends of each bill is unquestionably to render the same service to the needy widow.

Massachusetts deserves credit for being the first state to preface mothers’ pension legislation with a formal study of existing conditions. The Legislature of 1912 authorized the appointment of a commission “to investigate the question of the condition of widowed mothers within the commonwealth having minor children dependent upon them for support,” and to report to the succeeding Legislature “as to the advisability of enacting legislation providing for payments by the commonwealth for the purpose of maintaining such minor children in their homes.” The report of the commission giving its findings and recommending legislation based thereon has been published as is stated elsewhere in this issue,[2] David F. Tilley, one of the members of the commission, dissenting from the conclusions of the majority.

The success or failure of the mothers’ pension movement must depend largely upon our ability to avoid the mistakes which have characterized outdoor relief and other gratuitous payments to individuals from the public treasury, and to read into the proposed remedy a new and dignified meaning which outdoor relief has never had. It may be that both these ends will be difficult to attain. Certainly they can only be attained after the most careful study of the operation of outdoor relief, both public and private, to ascertain to what extent it has succeeded or failed and why. Such a study has long been necessary in the interests of the poor and of efficient relief work. To be successful it cannot be hasty, inexpensive or inexpert. Quite as important as this study of outdoor relief will be a study of the conditions under which children are admitted to institutions which must be undertaken with much the same end in view.

Those who have felt the need of more facts before enacting mothers’ pension legislation have been much interested in the study which Massachusetts has been making. If all the possibilities of such a study were realized in this report, a good many of our stumbling blocks would be removed. The existing outdoor relief machinery, public and private, an analysis of its success or failure and a standard for future procedure would all have been revealed.

The report of the Massachusetts commission, however, gives us very little help. It is marked by evident earnestness of purpose; but its conclusions are of little value because they represent in almost every case inferences from inadequate data. To a large extent this is to be charged to the commission’s inadequate resources; but whatever the reason the report as it stands does not give us a model for other states. It does not give us even a clear relation between the commission’s own findings and their recommendations. Because the right kind of an outdoor relief study is necessary and because the example of Massachusetts is likely to be followed by other states, it is important to subject this report to somewhat critical examination.

The commission’s method of study was five-fold:

1. A questionnaire to fifty-seven child helping societies and several public departments caring for dependent children as to the circumstances under which the children in their care were committed.

2. A questionnaire to various children’s agencies asking why children are separated from their mothers in poverty.

3. A questionnaire to public and private relief agencies asking for “the total income and the sources thereof, together with certain other facts in each widow’s family receiving through it (the agency) regular relief” for a definite period.

4. Special study of the Juvenile Court records of Boston and of the results of a day nursery investigation.

5. A use of analogies, observations and “reasons of a non-statistical kind” which suggest the desirability of legislation granting pensions to mothers.

Methods 1 and 3 brought the statistics upon which the chief conclusions of the report are based. But the commission itself by a series of statements regarding their accuracy robs one of any confidence in the results obtained. For example, these statements appear in the discussion of the statistics received from relief agencies:

“Because of its small appropriation it [the commission] was enabled to make a much less detailed and exact statistical study of the position of these widows than would have been desirable.”

“The resources of your commission did not permit it to secure its information by the personal visit of an investigator, hence the information must be less accurate than it might otherwise have been.”

“The commissioners believe that despite the limited accuracy of some of their relief statistics further study of the relief given by charities is not necessary.”

Moreover, regarding the information gained from the children’s agencies as to the causes for the removal of children from their homes, it may be doubted whether these agencies are competent 135witnesses. The standard of work done by the public agencies and many of the private agencies for the care of children in Massachusetts is unusually high. It may be doubted, however, whether any such agency after the most careful preliminary inquiry is fully able to determine the real economic status of a family which is usually a matter that requires long acquaintance. Many of these societies receiving children who have been removed from their mothers have very little first hand information as to the reason for it. In fact, the report itself, in discussing the information secured through this questionnaire regarding the insurance carried by the families, states: “The fact that the children’s agencies failed to answer this question in so many cases was undoubtedly because they did not possess the information.” For the same reason it is doubtful if they were competent witnesses on many other points calling for knowledge of what happened before the children came into their care.

The statistics secured through method 3 are condemned even more directly. After information had been secured through the questionnaire to public and private relief agencies regarding 1,258 families, Mr. Tilley of the commission arranged for a special study of one hundred of these in their own homes by trained visitors in the service of the State Board of Charity. These studies revealed conditions completely at variance with those stated in the returns received from the agencies themselves. The report itself comments: “It is clear that many records previously received from the overseers, especially, but also from others, were glaringly incorrect.”

It is hardly possible to put confidence in conclusions based upon data whose inaccuracy is so clear. It does not become any more possible when the inaccuracy is frankly conceded by those who reach the conclusions.

Another method of study used by the commission—the compilation of analogies and other non-statistical reasons for proving its case—is rendered impotent in much the same way. In a carefully developed argument the report draws an analogy between the proposed subsidy scheme for widows and the industrial accident compensation plan. “The situation of dependents of men killed by industrial accident is scarcely distinguishable from that of these widows.... Consequently, widows through death of husbands by disease or other non-industrial cause should be dealt with by a similar principle.”

After developing this analogy somewhat elaborately, however, the report says: “The commission rejects the principle of payment by way of indemnity of loss,” apparently abandoning the workmen’s compensation analogy just after making it serviceable.

It would not be difficult to point out other traits which are fatal to the report as a basis for scientific action, for example, its constant introduction of important conclusions with such expressions as “it is obvious,” “the inference is,” “it is not unlikely,” “so far as information was obtainable” and “important inferences are possible.” Moreover, when conclusions are based upon statistics compiled from different sources by different persons with different standards and possibly different interpretations of the questions asked, a report giving these statistics and the conclusions reached should give also a copy of the schedule used in gathering them. The report does not include the commission’s schedule.

With the purpose of the commission to point the way to the adequate assistance of widows most of us like Mr. Tilley, who submits a minority report, are in complete accord. During recent years our enlarging conceptions of social treatment have condemned utterly much of our supposedly efficient work in family and individual reconstruction. There is a widespread conviction of sin in this matter and an earnest searching for the remedy. The mothers’ pension movement is no doubt a result of this; but the conviction of sin and the earnest search are true of many to whom mothers’ pensions seem a remedy of doubtful immediate value.

If we have failed in our relief work, the children of the widow are not the only ones who have suffered. Upon the children of disabled fathers, of incompetent and neglectful parents, of all those tragic families who fall outside the commission’s category of “worthy,” our sins are visited still more heavily. The commission was charged only with the duty of studying the condition of widows; but it seems to have taken some note of families of other types. We read: “Consistently, widows through death of husbands by disease or other industrial cause ... deserve an utterly different kind of treatment from that accorded to the lazy and shiftless, the victims of drink, gambling or other dissipation or persons in transitory or emergency destitution. The commission does not believe that the same persons who administer the general poor law should alone determine the aid for worthy widows. Administration of such aid is sufficiently complicated, difficult and frequent to deserve separate care.” It might be noted incidentally that the cause of a husband’s death is not always a satisfactory test of a wife’s moral habits, and that “widows through death of husbands by disease, etc.” are not infrequently of the unsatisfactory type described by the commission. But a still more important comment is the following from Mr. Pear of Boston:

“It is well understood by social workers that those whom your correspondent terms the 136incompetent, and willingly leaves to the care of overseers of the poor are really in need of the most skillful ministration. They too have children. To assume that they may well be left to officials considered incapable of caring for respectable widows is evidence of a complacency which social workers cannot share.”

The report of the commission gives us much that suggests the fact of our failure to provide adequately or helpfully for the families of widows, a fact of which we had already become conscious. What we need, however, is not so much evidence of the fact of failure as a clear understanding of why we have failed. Why have public outdoor relief and private charity conceived in as deep an interest in the destitute widow as any mother’s subsidy program, failed to satisfy either the widow or the charitable or society at large?

The failure has rarely been due to lack of aggregate resources. Nobody familiar with the enormous totals spent for relief, public and private, could doubt that. It must lie somewhere in the quality of the service which brings relief with it. To determine just where it does lie calls for a study requiring money, time and the sure touch of somebody who knows what to look for. The mothers’ pension schemes which the various states have worked out give us very little that is new or of higher promise in the service that goes with relief. The subsidy plan that follows the study of the Massachusetts commission is no exception.

Few institutions have been subject to more criticism than public outdoor relief. No institution has been under fire so long with so little real effort to find out what makes it criticizable. It may well be that public assistance in some form is indispensable in this country and will be made to yield the results we seek. If so, its administration must be revolutionized. Giving existing outdoor relief officials new duties and responsibility to a new authority for part of their work, which is an important part of the proposal resulting from the Massachusetts report, will not revolutionize it. Nor will the giving of new names to old practices not otherwise shorn of the defects which popularize the new name do so. Again and again we have started with a clear call to do justice to the widow. Every time we try to translate our zeal into legislation we come square up against our outdoor relief machinery. Some one of these United States has a golden opportunity to make a study which will point the way to justice not only for the widow and her children but for every other person, old or young, who through our stupidity or his own fault, or both, finds himself forced to seek assistance. But the Massachusetts report does not point the way.

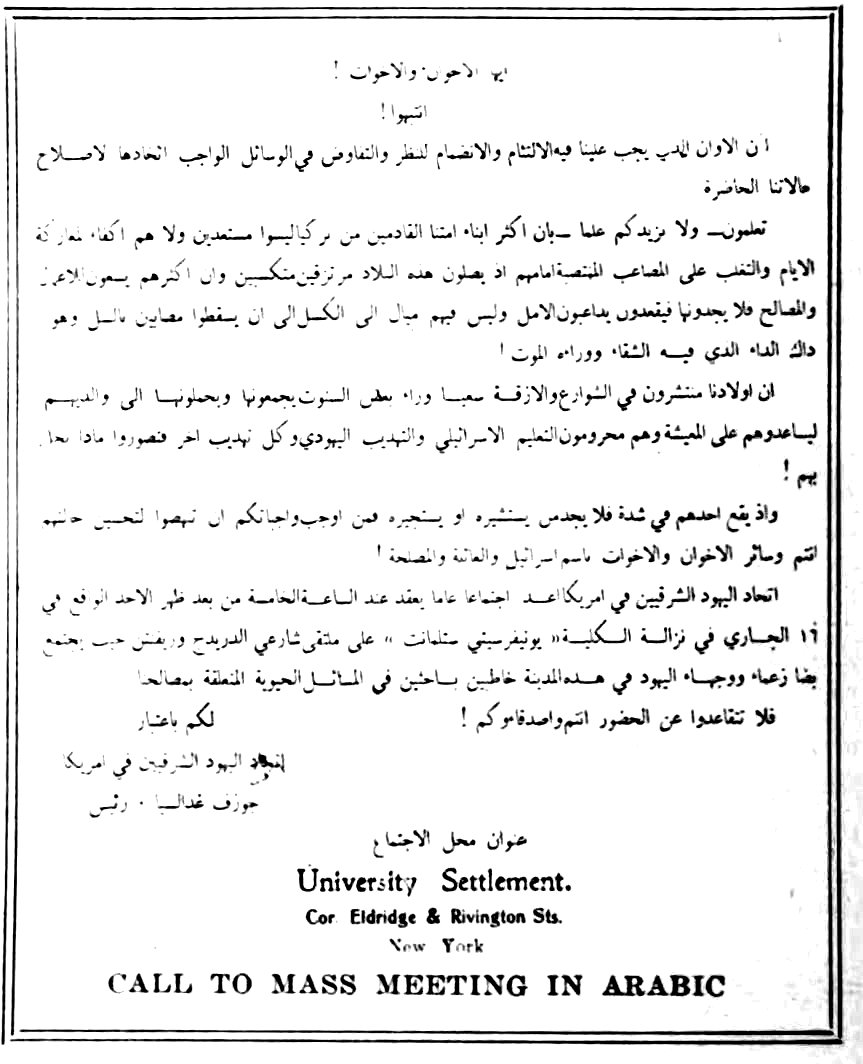

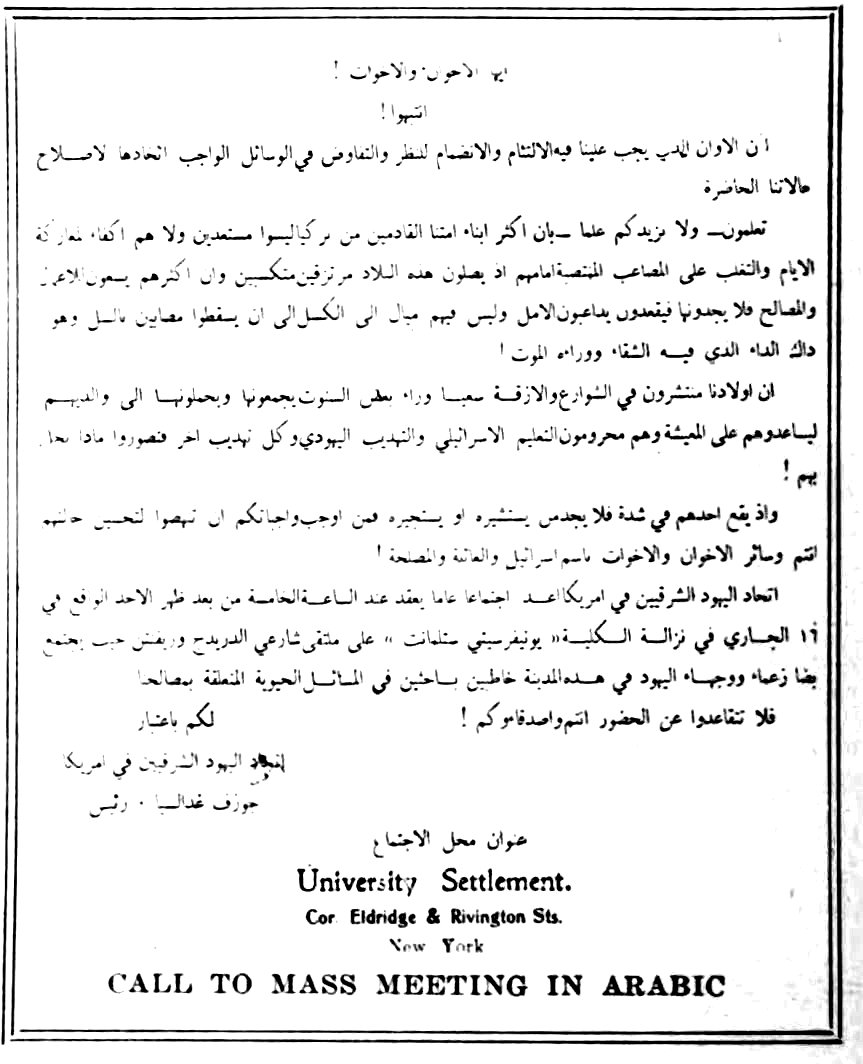

For four years New York has had a steadily growing colony of Castilian speaking Oriental Jews. The major part of them speak a Spanish dialect known as Ladino, but use Hebrew characters in writing. Knowing no English, they have lived in isolation, the largest group between Essex, Rivington, Christie and Canal streets. The rest are east of Lenox avenue in about twenty blocks north of 100th street.

The biggest step toward the Americanization of this group, which now numbers 15,000 and is not yet too large or scattered to be handled by a group plan, was the calling at the University Settlement last month of a mass meeting of the race. Here Joseph Gedalecia, manager of the Free Employment Agency for the Handicapped established by the Jewish community of New York, and president of the Federation of Oriental Jews, and other speakers proposed plans for lectures on American institutions and opportunities and suggested classes in English for the adults of the race.

In 1492 or thereabouts persecutions drove from the shores of Spain the Jewish merchants and scholars to whom the nation owed not a little of its development. They were welcomed by the Mohammedans and settled both in European Turkey and on the Asiatic coast. Most of the settlements of refugees preserved their Castilian speech, and the Ladino dialect, which they use today, is only slightly mixed with Greek or Bulgarian or Turkish or Arabic words, according 137to the section of the Turkish empire in which they happened to settle.

THE CALL IN LADINO

It is high time for us to come together and discuss ways and means to improve our conditions. Most of our people come to this country from Turkey and the Orient not altogether prepared for the struggle for existence that awaits them. A good many remain idle, or their work is intermittent, and others, again, work in surroundings not conducive to good health, nor is the remuneration sufficient to enable them to earn a decent livelihood, resulting in time in poverty, and in some cases our people are obliged to live in congested surroundings with disastrous effect on their health, and some are becoming tubercular. A good many of our children do not attend religious school and roam the streets without having religious training or the ideals of our religion inculcated in them, which may prove disastrous to Judaism and good citizenship. No central bureau of information for our people is available when they are in need of advice of any kind.

Therefore we appeal to you for the sake of yourself, your families and your children, as well as for the sake of Israel and your country, to attend a mass meeting which our federation has arranged to be held on Sunday, March 16, at the University Settlement where leaders of our community and other prominent men will discuss the issues affecting your interests.

Don’t fail to attend and urge your friends to do the same.

FEDERATION OF ORIENTAL JEWS OF AMERICA,

Joseph Gedalecia, President. A. J. Amateau, Secretary.

These Spanish Jews preserved their standing as merchants, artisans or even small semi-professionals. In some towns, notably Salonika, they came to form the bulk of the population. They were seldom persecuted as they had no suppressed nationalism to defend against an invader. They never sank to the level of the native peasantry. Though materially comfortable, their intellectual development stagnated, under Turkish discouragement of education, until the young Turk movement of a few years ago. This was accompanied by a spread of popular education and with it knowledge that there was a world outside their own particular corner of the Orient. Ambition and a desire to see the world stimulated an Oriental Jewish migration which is largely responsible for their presence in New York city. It is almost the only Jewish migration to America that was not due to poverty or persecution. The Spanish Jews chose America as their place of pilgrimage in the face of the fact that the Spanish government has recently sent representatives to Turkey for the purpose of inducing them to return to Spain, an evidence that that country believes them to have qualities that would be an asset to the country of their choice.

The present westward migration of the Spanish Jew had less to offer than their migration eastward five hundred years ago. In New York their isolation has been complete, for the Yiddish speaking East Side Jew does not understand them any better than does the American, and rather despises their lack of intellectual attainments.

In physical equipment these people are superior to the Russian Jew; they have strong, handsome physiques. The men have drifted to day labor rather than to the unwholesome work of the garment trades. The girls alone are in these trades; it is said, indeed, that they have usurped the whole of the East Side kimono work from the Russians. Free from the weakening effect of European persecution, the Ladino-speaking Jews have shown even in their short and handicapped history in America so far, a daring business sense which enables them to point to half a dozen American millionaires of their race. The Russian Jew among his million immigrants can point to scarcely more.

It is to give scope to these native abilities by adapting them to American conditions that Mr. Gedalecia and other leaders of the race have for four years been working up to the mass meeting of last month. This was held under the auspices of the Federation of Oriental Jews, a union of eighteen benefit societies which the Spanish and Portuguese Sisterhood and the North American Civic League for Immigrants were largely instrumental in forming about three years ago. Night classes for Ladino Jews have been opened in two public schools. Intensive work has been done by the Industrial Removal Office, also, in distributing individuals in other parts of the country besides New York or sending them to Panama, Central and South America and the 138Philippines, where their antique Spanish dialect survives and where, without the handicap of language, in more than one case, beginning as peddlers, they have become merchants. Many of those who have succeeded in business import their goods from the United States, thus becoming a medium of bringing about business relations between this country and its Latin-American neighbors.

The fourth report of the commissioner of charities of the new state of Oklahoma is an interesting document and much of the work reported is unique for it is work not done in a similar way or not done at all in any other state.

The plan of having a single commissioner do work ordinarily done by a secretary and a board exists only in two states—New Jersey and Oklahoma. In Oklahoma the work has been developed along some lines that are intensely interesting, although it seems doubtful whether the conditions anywhere else will lead to this plan being copied.

When Indian Territory became a part of Oklahoma, the lands were allotted in severalty to the Indians of the various tribes. Much of the land is almost worthless, but there is a great deal that is valuable because of the presence of oil, deposits of asphalt, building stone, coal, etc., while a large part of the old Indian Territory is among the best agricultural land of the state.

The temptation to exploit these Indian lands, to purchase them from the Indians at a tenth of their value, has been somewhat offset by the action of the United States government. But among the Indians were a large number of orphans. Their land has been cared for by guardians, some of whom have succeeded in getting themselves appointed, with motives anything but benevolent toward their wards.

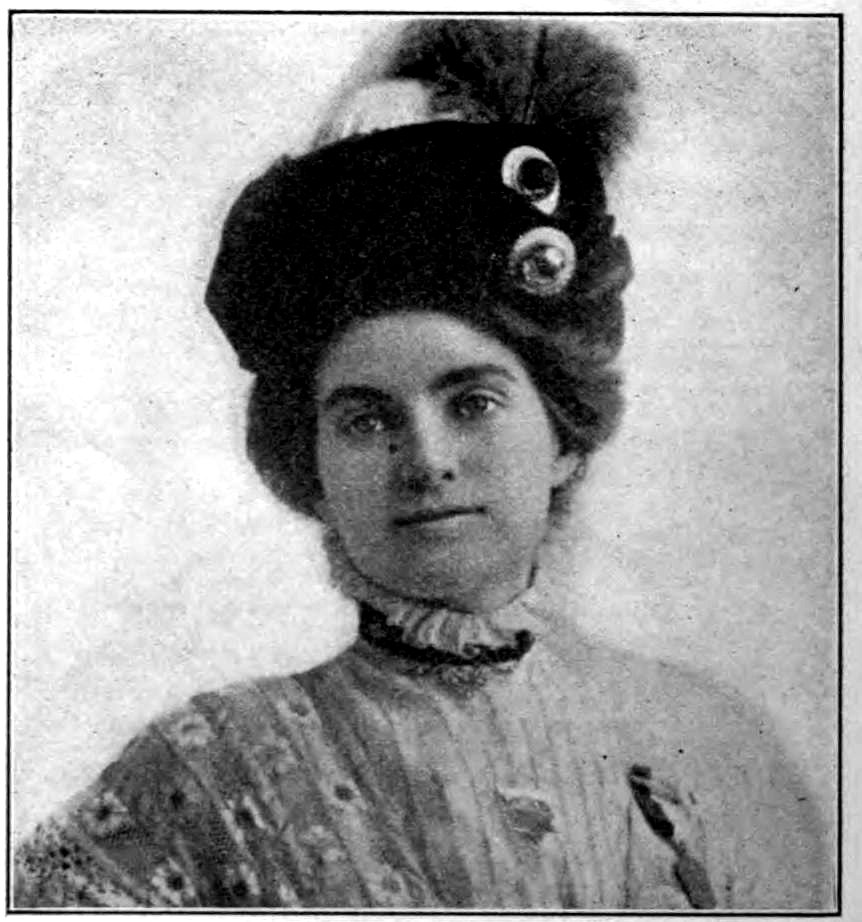

KATE BARNARD

The Oklahoma charities commissioner whose administration has secured the return of a million dollars to Indian orphans under incompetent or dishonest guardians.

The legal department conducted under Kate Barnard, the commissioner, by Dr. J. H. Stolper, has taken up a vast number of Indian orphan cases. The results have been positively surprising. The legal department has not failed in one single case. The entire amount of money wrested from incompetent or dishonest guardians and returned to orphans has been nearly $950,000. The value of the land is not stated but it is probably several times as much as that of the actual cash returned. The number of minors represented in the report is 1,373 and the number of cases 1,361. These were tried out in thirty-six different county courts. The cost of handling this enormous amount of legal work as well as all the legal work in the office was less than $6,000 which covers the salary of the general attorney, that of one stenographer and the necessary travelling expenses.

The commissioner suggests that, as there seems to be some difficulty in appropriating sufficient money for the support of her office, she should be allowed to charge a uniform fee of $5 for each case of the kind which is undertaken, that fee going to the support of the Department of Charities and Correction. At present no fees are charged from any of the minors.

Beside acting as next friend of orphan children, the general attorney of the commission has been for a year or more acting as public defender. It seemed to the Legislature that there was as much need of a public defender as of a public prosecutor and accordingly, at the last Legislature a law was passed creating the office. This the governor vetoed, but his veto was not in time to defeat the bill. However, the question of the salary was not taken up and Dr. Stolper, attorney for the commissioner, was appointed public defender and has been doing the work. A number of interesting instances of miscarriage of justice which the public defender has been able to remedy are given in the report.

The report gives the usual account of inspection of institutions both state and county and shows that the commissioner with her very limited office and inspection force was able to do much more work than would be expected. 139On the whole it seems as though the plan of a single headed commission is a success in the state of Oklahoma.

Attention has again been directed to the unsatisfactory conditions which prevail in the administration of quarantine inspection at the port of New York by the report of a special committee of the New York Academy of Medicine.

This report, which was recently made public, strongly advocated the national control of quarantine from “the point of view of convenience, efficiency and uniformity of administration, economy and law.” The subject aroused discussion in the newspapers a few weeks ago because the chairman of Governor Sulzer’s commission for the investigation of state departments urged the transfer of this function to the federal government.

In the discussion of this recommendation, several important points have been overlooked. For example, there is some significance in the discrepancy between the large sums spent by New York on the quarantine station, which protects the country at large, and the small amount expended for the State Health Department, upon which rests the protection of the citizens of the state. Doubtless, as has been pointed out, the fees charged steamship companies can be increased so that the state will not be required to make any annual appropriations for the maintenance of the quarantine station but the health officer of the port has asked for an appropriation of about $1,800,000 for needed repairs and improvements. About $180,000 is appropriated for the State Department of Health each year. This constitutes practically all the money spent by the state for the protection of the health of its 9,000,000 citizens. Out of it must be paid all salaries and expenses of administration, the cost of collecting vital statistics, maintaining laboratories for research and for the production of diphtheria antitoxin, the control of epidemics, the inspection of water supplies and, in short, all the work in the prevention of disease in which the state is engaged. If the Legislature grants the $1,800,000 which the health officer of the port requests, it will give him an amount equal to that expended during ten years for safeguarding the health of those residing in the state.

Closely related to this aspect of the question is the fact, which has received little attention, that some of the largest immigrant-carrying lines do not enter New York at all but dock at Hoboken and Jersey City. Last year more than 36 per cent. of all the passengers who arrived at this port from Europe landed in New Jersey. The following table shows the passengers brought during 1912 by steamship lines having docks at Hoboken and Jersey City:

| Steamship Lines | Cabin | Steerage | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| North German Lloyd | 51,920 | 118,803 | 170,723 |

| Hamburg American | 38,033 | 98,043 | 136,076 |

| Holland American | 18,611 | 33,877 | 52,488 |

| Scandinavian American | 5,265 | 13,064 | 18,329 |

| Lloyd Sabaudo | 652 | 7,119 | 7,771 |

| 114,481 | 270,906 | 385,387 |

Less than 30 per cent. of the immigrants who arrived at this port during the year remained in this state, a large proportion landing in New Jersey, being examined at Ellis Island and going west by one of the railroad lines terminating at Jersey City. They were distributed over a wide area and it cannot be denied that it is chiefly for the protection of distant states that New York’s expensive quarantine is maintained.

Much has been said about the advantages to commerce of the state control of quarantine at the port of New York. If $300,000 are collected during 1913 in fees from steamship companies, the amount will equal the earnings on $7,500,000 of invested capital. In other words, an amount of capital which would purchase ten large freighters must be set aside to meet the quarantine dues at this port for one year. If ten such vessels were tied up at one of the piers in this city for a year, as an object lesson, we would not hear very much about the advantages to commerce which local control of quarantine insures.

The tax rate in the Borough of Manhattan for 1911 was 1.72248. At such a rate it would be necessary to tax $17,000,000 of capital to raise $300,000 a year. This means that a tax equal to that rate on real estate in the Borough of Manhattan has to be levied on $17,000,000 of the capital of steamship companies to pay for a quarantine station, the cost of which should be borne by the country which it protects.

Another phase of the question which has not been touched upon is the relation between quarantine and the medical control of immigration. At ports where the United States Public Health Service administers the quarantine law and conducts the medical inspection of immigrants, the two functions are performed under conditions making each more efficient and also reducing interference with commerce to a minimum. The medical inspection of immigrants at Ellis Island, which is performed by medical officers of the United States Public Health Service, constitutes the second line of quarantine defense and not a few cases of small-pox and typhus fever which have escaped observation at the state quarantine station have been detected in the medical examination at Ellis Island.

If both functions were performed by the 140Public Health Service at this port the work could be carried on much more effectively and with benefit to the immigrant—a factor which no one seems to have considered. When cases of scarlet fever, measles, diphtheria and the other contagious diseases of childhood were taken off vessels at the state quarantine station, children died without their mothers, who were detained at Ellis Island, even being able to visit them once during their illness. At the same time a magnificent new group of hospitals for contagious diseases remained idle at Ellis Island. No better example of the danger and inutility of divided control could be found than this.

In attempting a review of the social legislation passed in New Jersey during the administration of Woodrow Wilson, it is difficult to disentangle his share in its accomplishment. It is also difficult to distinguish between purely political measures and those which would be of special interest to social workers.

Measures for better primaries and corrupt practices acts had been introduced several times while he was still president of Princeton University. The Employers’ Liability Act was recommended by a commission named by his predecessor, Governor Fort. The Consumer’s League and Federation of Women’s Clubs had been working for a long time to improve laws relating to the hours and condition of women and children in industry. At the same time, no one who has been in touch with the marvelous change which has brought New Jersey to the first rank of progressive states can fail to realize that in practically one session of the Legislature the astounding insight, force and influence of one man achieved what might otherwise have taken years to accomplish. It must be remembered that almost all the important Wilson legislation was passed by the Legislature of 1911, when the House was Democratic. The Senate, although Republican, was brought into line by the governor. The session of 1912, when both Houses were Republican, produced little important legislation, and the Legislature of this year up to the time when President Wilson resigned to assume his duties at Washington passed but one important measure—that regulating the trusts incorporated in New Jersey. The jury reform bill is still under discussion and will be the subject of a special session of the Legislature in May.

I shall attempt to give a list of the laws primarily relating to social legislation, but the great reforms which will always be associated with Wilson’s name, although specifically political in their nature, must have a vast influence on the whole structure of the state. If our politics become cleaner, inefficiency and graft must gradually disappear and the citizens will grow to feel that they can trust their representatives with larger and larger sums to be used for the relief and care of the wards of the state.

Among these laws perhaps the most important are the following:

Limitation of the working hours of women to sixty a week, the first regulation of any kind for New Jersey women in industry; appropriation for the first time for the Woman’s Reformatory which was urged in Governor Wilson’s message to the legislature of 1911; standardization of trained nursing; establishment under the State Board of Education of special classes for children three years below the normal and also special classes for blind children; provision for the punishment of any person controlling a public place of amusement who permits the admission of children under eighteen years without a parent or guardian, and for any adult who encourages juvenile delinquency; passage of an act requiring that no pawnbroker shall receive any article from any person under the age of eighteen years; prohibition of furnishing cigarettes or tobacco to minors; provision for parental schools or house of detention for juvenile offenders; appointment of a special county judge for juvenile and domestic relation cases; enactment of an act placing New Jersey in the front rank in the campaign against tuberculosis; prohibition of the use of common drinking cups; establishment of free dental clinics; regulation of moving picture shows; employment of prison labor on roads; enactment of a comprehensive and scientific poor law; regulation of weights and measures; passage of an indeterminate sentence act; abolition of contract labor in all prisons and reformatories.

In addition to this legislation, it may be interesting to mention the appointment of commissions on prison labor, employers’ liability, city government, public expenditures, ameliorating the condition of the blind and playgrounds in all cities and villages. Governor Wilson also made several excellent appointments with entire disregard of politics, particularly those of his commissioner of education and his commissioner of charities and corrections. For the first position he brought Dr. Calvin Kendall from Indiana, and for the second he named Joseph P. Byers. Excellent appointments were also made to the boards of managers of the various state institutions.

Governor Wilson with his wife and daughter made a tour of inspection of all our state institutions, which in contrast to the usual perfunctory governor’s visit, was most valuable in bringing him in touch with the superintendents and with the various problems at the different institutions.

Francis Greenwood Peabody, Plummer professor of Christian morals in Harvard University, recently retired from its faculty after service extending over a generation.

To the observant public he is known chiefly as author of several works on social ethics, such as The Approach to the Social Question and Jesus Christ and the Social Question or as a preacher and speaker whose inspiring thoughts are clothed in remarkably well chosen words. At Harvard he was a college preacher, and had a leading part in changing the religious exercises of the College Chapel so that attendance was voluntary instead of required, and there were ministrations from clergymen of different denominations. He helped to place the divinity school on a board basis.

His chief work in the academic world was the significant one of beginning and developing systematic instruction in the application of principles of ethics to pressing social problems. Just thirty-three years ago he began a course of lectures on that subject in the divinity school of Harvard. Four years later it was made a general university course for advanced students. In this said Mr. Peabody, there is “a new opportunity in university instruction. With us it has been quite without precedent. It summons the young men who have been imbued with the principles of political economy and of philosophy, to the practical application of those studies.”

That course at Harvard, with the instruction begun at Cornell in 1884 by Frank B. Sanborn, under President White, was the beginning of academic work in this country, specialized and practical, in that field, and at Harvard it has continued, a systematic development. It is within the division of Philosophy. This means no lack of appreciation of the economic forces in society, but it points to the broad highway to solving vital problems though the field of ethics. This teaching so won the confidence of a generous donor, prominent alike in business and philanthropy, that the erection of Emerson Hall was made possible, with ample quarters for the Department of Social Ethics. Thus Mr. Peabody leaves the department which he has built up on the solid ground of continuity.

Among the hundreds of young men who have taken Mr. Peabody’s general course and his seminary courses, many have been helped by him to be better citizens and neighbors. Not a few have carried stimulus caught from him into professional life in social service the country over.

The recent and really remarkable activity of Harvard students in social service, centering at Phillips Brooks House, was largely founded and fostered by Mr. Peabody. He has been identified with Prospect Union from its opening in 1891: a piece of university extension, in whose evening classes the teachers are college students and the students are all sorts and conditions of men from mercantile and industrial life in Cambridge. Long ago, he helped to start co-operative stores, a method of bringing forward democracy and thrift—which is none the less sound because many persons were not ready for it. He urged the trial in Massachusetts cities, under local option, of the foreign system of government administration of the sale of liquor—to which worse systems may yet bring us.

He was a leading founder of the Associated Charities of Cambridge. In these and many other ways he has brought the knowledge of a college professor, with warm interest, into the affairs of the community.

The social survey is gaining recognition as an instrument for community advance so rapidly that the new Department of Surveys and Exhibits of the Russell Sage Foundation, which was established last October, has found it necessary to increase its staff. The work of the department during its first three months has been largely advisory—defining surveys by specific illustrations, outlining the steps for selecting a representative committee to back a survey or an exhibit, assisting in the choice of subjects to be covered and estimating probable costs. The increase in the staff will facilitate an extension of this service and make more field work possible. The new members of the staff are Zenas L. Potter of New York and Franz Schneider, Jr., of Boston.

Mr. Potter is a graduate of the University of Minnesota where he specialized in administration of governmental problems. This was followed by a year’s graduate work at Columbia in economics and social economy, where he received the Toppan prize for the best work in constitutional law. After leaving Columbia he was field secretary of the New York Child Labor Committee for two years. He investigated the work conditions of children in the state, and in 1912 directed the cannery investigation for the New York State Factory Investigating Commission. The findings of this inquiry are being used in the campaign for better laws regulating child labor conditions in New York state.

Mr. Schneider, while taking courses leading to his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gave special attention to subjects in the field of public health and sanitation. Since 1910 he has taught in the institute, and will leave the position of research associate in the sanitary research laboratories to join the Department of Surveys and Exhibits. In the summer of 1911 he was employed in Kansas on special investigations into the bacteriology of the egg-packing industry, and during the summer of 1912 on an investigation into the fundamental principles of ventilation. For the last year he has helped edit the American Journal of Public Health and at present is health officer of Wellesley, Mass. The latter work is part of a plan which is being worked out with Prof. E. B. Phelps, also of the institute, to build up an organization to operate the Board of Health work of small towns in 142the neighborhood of Boston. The aim is to give these towns a service comparable to that of the large cities, a service which they alone could not afford.

A young sanitary inspector in a mid-western city had his suspicions of a new milk company. He never seemed to be able to catch the wagon as it drove into town, so one day he jumped on his bicycle and rode out to the farm to get a sample. The man was not there, and his wife said that they had no milk left on the place that morning. The inspector’s suspicions were more than ever aroused, and he made a search of ice boxes and cooling places, only to find no milk. It is a very easy thing for milk to disappear when an inspector turns in at the gate. Nothing daunted, therefore, he pulled down a pail from its peg, marched out to the pasture, cornered a cow, milked her, and, sample in hand, rode back to the city triumphant.

The health commissioner is wonderfully proud of this spirit of not-to-be-balkedness in his inspector. He has the makings in him of a master of public health. But the commissioner felt obliged to explain to his assistant with as sober a face as he could muster, that up to date in that part of the commonwealth they had not hitherto arrested a single cow for putting formaldehyde in her milk or for diluting it.

Childhood’s Bill of Rights, printed some time ago in The Survey[3], has developed an ever widening influence. One enthusiastic friend sent it during the past Christmas season to some forty foreign lands. V. H. Lockwood, author of the bill, is a busy Indianapolis attorney but he finds time for social service whether called upon to act as judge pro tem of the juvenile court, as the vice-president of the Children’s Aid Association, or on a committee of the State Conference of Charities. His special interest just now is the work of the vice committee of the Indianapolis Church Federation.

Mr. Lockwood, long ago, became interested in the juvenile court. He was frequently consulted by Judge Stubbs, the first juvenile court judge in Indiana, and for several years was one of his substitutes on the bench. Out of this experience grew the Bill of Rights which was jotted down in his notebook years ago. From it grew also the Children’s Aid Association, which Mr. Lockwood helped to organize for the purpose of saving children from being taken into court. He has also co-operated in drafting several of Indiana’s laws for the safeguarding of children, particularly those having to do with the juvenile court, contributory delinquency, the licensing of maternity hospitals and children’s institutions, and child labor.

MRS. V. H. LOCKWOOD

To Mrs. Lockwood, however, is due most of the credit in connection with Indiana’s child labor law. She has for several years been secretary of the State Child Labor Committee and has been active in other welfare work. Two years spent under the direction of the National Child Labor Committee in investigating conditions in Indiana armed her with facts which were used effectively before the two legislatures which considered the child labor bill. The first attempt met with defeat, but the next session passed the present law. Between the two sessions Mrs. Lockwood traveled over the state, working to educate the people through the clubs and schools. She is one of the lecturers of the Indiana Federation of Clubs, and takes a part in many branches of social welfare work in Indianapolis.

A Sunny Life: The biography of Samuel June Barrows, is the title of a volume which Little, Brown and Company are to bring out in April. The author is Mrs. Barrows. Readers of The Survey who knew the former president of the International Prison Congress, but who had only glimpses of his remarkable experiences as editor, congressman, minister, digger of Greek temples, and follower of Custer on the plains, will look forward to this record of the man by his comrade and fellow worker of fifty years.

Floyd J. Miller, who has been in newspaper work for six years, has left the staff of the Detroit Free Press to become financial secretary of the Detroit Associated Charities.

From the pages of John Gower, a correspondent of the New York Evening Post takes the following passage, in the hope that the trials of a housekeeper in the fifteenth century may bring consolation to the householder of today. Says the worthy Gower:

Man is so constituted as to require above all else food and drink. So it is no wonder if I speak of victualers, whose principle it is to deceive and to practice fraud. I will begin, as an instance, with the tavern-keeper and his wine-cellar.... If his red or white wine loses its proper color, he mixes it freely to procure the proper shade.... If I stop in to fill my flask, he gives me of his best wine to taste, and then fills my flask with some cheap stuff. He pretends to have any foreign vintage that one desires, but under divers names he draws ten kinds from the same barrel.... The poor people complain with reason that their beer is made from an inferior quality of grain, while good beer is almost as dear as wine. If you give an order for beer to be delivered at the house, the inn-keeper will send a good quality once or twice until he gets your trade, and then he sends worse at the same price.... Every one in the city is complaining of the short-weight loaves the bakers sell, and wheat is stored with the intention to boost the price of bread.... Whether you buy at wholesale or retail, you have to pay the butcher twice the right price for beef and lamb. Lean beef is fattened by larding it, but the skewers are left in and ruin the carver’s knife.... To fetch their price, butchers often hold back meat until it is bad, when they try to sell it rather than cast it to the dogs.... Poulterers sell as fresh game what has been killed ten days before(!)... For my own part, I can dispense with partridges, pheasants, and plovers. But capons and geese are almost as high nowadays as hens.

Yet, if all those of whom I have spoken agreed to be fair and just, there would still be unfairness in the world. For even laborers are unfair, and will not willingly subject themselves to what is reasonable, claiming high wages for little work; they want five or six shillings for the work they formerly did for two. In old times workingmen did not expect to eat wheat bread, but were satisfied with coarser bread and with water to drink, regarding cheese and milk as a treat. I cannot find one servant of that sort now in the market (i. e., intelligence office!). They are all extravagant in their dress, and it would be easier to satisfy two gentlemen than one such ill-bred servant. They are neither faithful, polite, or well-behaved. Many are too proud to serve like their fathers.... The fault lies with the lethargy of the gentry, who pay no heed to this folly of the lower classes; but, unless care be taken, these tares will soon spring up, and the insurgence of these classes is to be feared like a flood or a fire.

The trouble is that no one is satisfied with his own estate; lord, prelate, commoner—each accuses the other. The lower classes blame the gentleman and the townsman, and the upper classes blame the lower, and all is in confusion.... The days prophesied by Hosea are come to pass, when there shall be no wisdom in the earth. I know not if the fault lie with laymen or churchmen, but all unite in the common cry: “the times are bad, the times are bad.”

Annie Laws (Kindergarten Review) believes that she can trace the social spirit of the kindergartner as an important factor in stimulating, and in some cases, even initiating, many of the social movements of today, among them playgrounds, social centers, vacation schools, public libraries, mothers’ clubs and school and home gardens.

The relation between the kindergarten and the big world outside the kindergarten Miss Laws states as follows:

Some one has said that “the primary aim of the kindergarten is to create a miniature world which shall be to the child a faithful portrait of the greater world in its ideal aspects.”

If the kindergarten can bring to each and all of us its aid in helping us to create for ourselves a miniature world, which shall be a faithful portrait of the greater world in its ideal aspects; and if it can aid in making us content to give to our communities the service for which we are best fitted, and can teach us to so live that not so much social efficiency as social reciprocity shall be our aim and purpose, then we shall all agree to give to the kindergarten its true place as one of the most valuable factors of social life and social work of the present time, one worthy of our best thought and effort.

144The following striking comparison is from The Road from Jerusalem to Jericho (Good Housekeeping), a plea by Frances Duncan for votes for women on the ground that woman is the ideal samaritan; man the priest and the Levite who at the present time alone has the power, but lacks the inclination, to stoop to care for the injured by righting social wrongs, especially those affecting women. Miss Duncan tells of a haunting drawing by Frederick Remington:

The central figure is that of a man who has been taken by a band of Indians; four or five of his captors are about him, and you see the relentless faces lit with the grim joy of capture. Around the man’s neck a noose hangs loosely; about him he sees only the inexorable faces, the wide stretches of the plains, the silences in which there is no help. The man looks past the plains into the ghastly future that is just ahead. The picture is called “Missing.”

In this country hardly a day goes by but in it is enacted a tragedy worse than that of Remington’s picture; and it’s called by the same name. Take up a paper almost any day in New York and you read of the disappearance of a girl of fourteen or fifteen or sixteen, or of the suicide of a girl who has been caught in the horrible undertow from which, as far as society is concerned, there is no return. Within the last year, on the various routes between New York and Chicago, no less than nine hundred and sixty girls have disappeared.

A woman of philanthropic tendencies was paying a visit to a lower East Side school. She was particularly interested in a group of poor pupils and asked permission to question them.

“Children, which is the greatest of all virtues?”

No one answered.

“Now, think a little. What is it I am doing when I give up time and pleasure to come and talk with you for your own good?”

A grimy hand went up in the rear of the room.

“Please, ma’am, youse are buttin’ in.”—The Delineator.

The Ladies Home Journal believes that, no less than factory and commercial worker, the oldest of home workers—the “domestic”—should be protected by standardization of wages, hours and living conditions. An editorial in the March issue says:

There is today practically no standard of wages for domestic help. The wages vary in different cities: in fact they vary in a city and a neighboring suburb. One “employment agency” fixes one wage: another settles on a different wage. There is no equitable fairness either to mistress or servant. No one really knows what is fair. The same haphazard system applies to hours of work. Neither employer nor servant knows what constitutes a fair day’s work for a cook or a maid. The whole question should be threshed out and adjusted to a standard just as are other branches of labor. Whether the eight-hour idea can be effectively worked out in the home is a question: more likely we shall have to begin on a ten-hour-day basis and gradually adjust ourselves to an eight-hour schedule with extra pay for extra hours. Employer and helper should know exactly where each stands on both questions of hours and wages. There is no further reason why, gradually, the system of our servants living outside of our homes should not be generally brought into vogue—the same as the working women engaged in all business lines. It is now done in “flats” and “apartments” where there is no room for servants’ quarters, and there is really no reason why the system should not be followed in houses where there is room. This would give a freedom of life to the servant that she does not now have, and which lack of freedom, and hours of her own and a life of her own, is the chief source of objection to domestic service, while the employers’ gain would lie in the fact that our homes could be smaller in proportion to the number of servants for whom we must now have rooms. In other words there seems to be no practical reason, except a blind adherence to custom, why the worker in the home should not be placed on exactly the same basis as the worker in the office, the store or the factory. That this idea is destined to come in the future, and in the near future, admits of no doubt. Of course it will take some time to consider all the phases of the matter that make home service different from office or store service. But we shall never solve the question of domestic service until we first place it on a practical business basis.

In the library of Clark University the volumes of Charles Booth’s Life and Labor of London are bound under the title A Survey of London.

By Warren H. Wilson. The Pilgrim Press. 221 pp. Price $1.25; by mail of The Survey $1.35.