Washington Irving

[From a Daguerreotype by Plumbe.]

[From a Daguerreotype by Plumbe.]

There is a freshness about the fame and the character of Mr. Irving, no less than about his writings, which enables us to contemplate them with unabated delight. Few men are so identified personally with their literary productions, or have combined with admiration of their genius such a cordial, home-like welcome in the purest affections of their readers. We never become weary with the repetition of his familiar name; no caprice of fashion tempts us to enthrone a new idol in place of the ancient favorite; and even intellectual jealousies shrink back before the soft brilliancy of his reputation. In the present Number of our Magazine, we give our readers a portrait of the cherished author, with a sketch of his sunny residence, which we are sure will be a grateful memorial of one, to whom our countrymen owe such an accumulated fund of exquisite enjoyments and delicious recollections. We will not let the occasion pass without a few words of recognition, though conscious of no wish to indulge in criticisms which at this late day might appear superfluous.

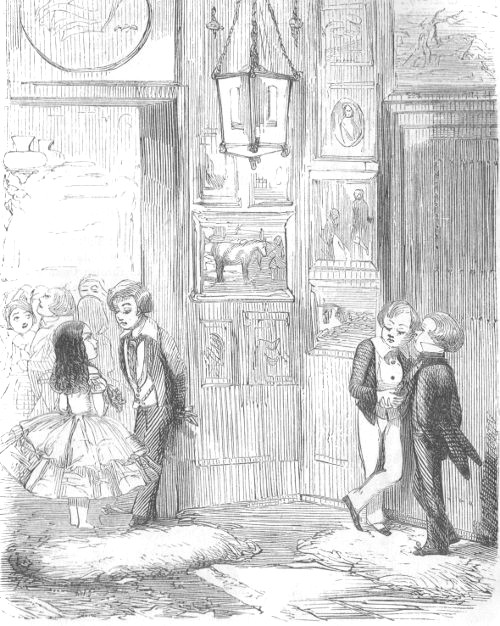

The position of Mr. Irving in American literature is no less peculiar than it is enviable. With the exception of Mr. Paulding, none of our eminent living authors have been so long before the public. He commenced his career as a writer almost with the commencement of the [Pg 578] present century. The first indications of his rich vein of humor and invention that appeared through the press, were contained in the Jonathan Oldstyle Letters, published in the Morning Chronicle in 1802, when he was in the twentieth year of his age. His health at this time having become seriously impaired, he spent a few years in European travel, and soon after his return in 1806, he wrote the sparkling papers in Salmagundi, which at once decided his position as a shrewd observer of society, a pointed and vigorous satirist, a graphic delineator of manners, and a quaint moral teacher, whose joyous humor graciously attempered the bitterness of his wit. It was not, however, till the appearance of Knickerbocker, that his unique powers, in this respect, were displayed in all their vernal bloom, giving the promise of future golden harvests, which has since been more than redeemed in the richness and beauty of the varied productions of his genius.

The lapse of years has brought no cloud over the early brightness of Mr. Irving's fame. He has sustained his reputation with an elastic vigor that shows the soundness of its elements. At the dawn of American letters, he was acknowledged to possess those enchantments of style, that betray the hand of a master. His rare genius captivated all hearts. His name was identified by our citizens with the racy chronicles of their Dutch ancestors, and soon became associated with local recollections and family traditions. Born in a quarter of the town, whose original features have passed away before the encroachments of business, he has witnessed the growth of his fame with the growth of the city. The memory of Diedrich Knickerbocker is now immortalized at the corners of the streets, and in our most crowded thoroughfares. Even the dusty haunts of Mammon are refreshed with the emblems of a man of genius who once trod their pavements.

With his successive publications, a new phase of Mr. Irving's intellectual character was displayed to the public, but with no decrease of the admiration, which from the first had stamped him as a universal favorite. The Sketch Book, Bracebridge Hall, and Tales of a Traveler revealed a magic felicity of description, with a pathetic tenderness of sentiment, that gave a still more mellow beauty to his composition; while his elaborate historical work, The Life of Columbus, established his reputation for unrivaled skill in sustaining the continuous interest of a narrative, and in grouping its details with admirable picturesque effect. His later productions, illustrative of Indian life, and his still more recent works on the history of Mahomet and the biography of Goldsmith, are marked with the characteristic traits of the author, proving that his right hand has lost none of its cunning, nor his tongue aught of its mellifluous sweetness.

It is highly creditable to the tastes of the present generation, that Mr. Irving retains, to such a remarkable degree, his wonted ascendency. Other authors of acknowledged eminence have arisen in various departments of literature, since he won his earlier laurels, and many of them since he has ceased to be a young man, but they have not enticed the more youthful class of readers from the allegiance which was paid to him by their fathers. The monarch that knew not Joseph has not yet ascended the throne. Indeed many of the most true-hearted admirers of Mr. Irving were not born until long after the Sketch Book had made his name a household word among the tasteful readers of English literature. This enduring popularity could not spring from any accidental causes. It must proceed from those qualities in the author, which are the pledge of a permanent fame. If a foretaste of literary immortality is desirable on earth, we may congratulate Mr. Irving on the possession of one of its most significant symbols, in the unfading brilliancy of his reputation for little less than half a century.

We have already alluded to the use made by Mr. Irving of the historical legends of our country. Nor is this his only claim on the American heart. He is peculiarly a national writer. He has sought his inspirations from the woods and streams, the lakes and prairies of his native land. No poet has been more successful in throwing the spell of romance around our familiar scenery. Under his creative pen the lordly heights of the Hudson have become classic ground. The beings of his weird fancy have peopled their forest dells, and obtained a "local habitation" as permanent as the river and the mountains. His love of country is a genial passion, inspired by the reminiscences of his youth, and quickened by the studies of his manhood. He is proud of his birthright in a land of freedom. His protracted residence abroad has never seduced him from the ardor of his first attachment to the American soil. His favorite writings are pervaded with this spirit. Yet he betrays none of the prejudices of national pride. His patriotism is free from all tincture of bigotry. He scorns the narrowness of exclusive partialities. With genuine cosmopolitan tastes, he gathers up all that is precious and beautiful in the traditions, or manners, or institutions of other lands, finding materials for his gorgeous pictures in the ancestral glories of English castles, and the splendid ruins of the Alhambra, as well as in the quaint legends of Manhattan, and the adventures of trapper life in the Far West. This singular universality has given him the freedom of the whole literary world. As he every where finds himself at home, his fame is not the monopoly of any nation. He has his circle of admirers around the hearth-stones of every cultivated people. Even the English, who are slow to recognize a melody in their own language when spoken by a transatlantic tongue, have vied with his countrymen in rendering homage to his genius. His evident mastery, even in those departments of composition which have been the favorite sphere of the most popular English writers, has softened the [Pg 579] asperity of criticism, and won a genial admiration from the worshipers of Addison, Goldsmith, and Mackenzie. In this respect Mr. Irving stands alone among American writers. Cherished with a glow of affectionate enthusiasm by his own countrymen, he has secured a no less beautiful fame among myriads of readers, with whom his sole intellectual tie is the spontaneous attraction of his genius.

His universality is displayed with equal strength in the influence which he exerts over all classes of minds. He has never been raised to a factitious eminence by the applauses of a clique. His fame is as natural and as healthy as his character, owing none of its lustre to the gloss of flattery, or the glare of fashion. His themes have been taken, to a great extent from common life. He has derived the coloring of his pictures from the universal sentiments of humanity. He is equally free from cold, prosaic, common-place hardness of feeling and from sickly and mawkish effeminacy. He loves to deal with matters of fact, but always surrounds them with the light of his radiant imagination. He exalts and glorifies the actual, without losing it in the clouds of a vaporous ideal. Refined and fastidious in feeling, he retains his sympathy with the most homely realities of life, chuckles over the luscious comforts of a Dutch ménage, and professes no philosophical indifference to the savor of smoking venison in an Indian lodge. With the curious felicity of his style, he uses no strange and far-fetched words. Its charm depends on the beauty of its combinations, not on the rarity of its language. He employs terms that are in the mouths of the people, but weaves them up into those expressive and picturesque forms that never cease to haunt the memory of the reader. Accordingly, he is cherished with equal delight by persons of every variety of culture. His fascinating volumes always formed a part of the traveling equipage of one of the most celebrated New-England judges, and they may be found with no less certainty among the household goods of the emigrant, and the resources for a rainy day on the frugal shelves of the Yankee farmer. They still detain the old man from his pillow, and the schoolboy from his studies. Under their potent charm, the merchant forgets his Wall-street engagements; the preacher lingers over their seductive sentences till the Sunday becomes an astonishment; the statesman is beguiled into oblivion of the salvation of his country; and the advocate is absorbed in the fortunes of some "roystering varlet," till his own forlorn client loses all chance of recovering his character.

The writings of Mr. Irving are no less distinguished by the truthfulness and purity of their moral tone, than by their delightful humor, and their apt delineations of nature and society. It is small praise to say that he never panders to a vicious sentiment, that he makes no appeal to a morbid imagination, and has written nothing to encourage a false and effeminate view of life. His merits, in this respect, are of a positive character. No one can be familiar with his productions, without receiving a kindly and generous influence. His goodness of heart communicates a benignant contagion to his readers. His mild and beautiful charity, his spirit of wise tolerance, the considerateness and candor of his judgments, the placable gentleness of his temper, and the just appreciation of the infinite varieties of character and life are adapted to mitigate the harshness of the cynic, and even to quell the wild furies of the bigot. His sharpest satire never degenerates into personal abuse. It seems the efflorescence of a rich nature, susceptible to every shade of the ludicrous, rather than the overflow of a poisonous fountain, spreading blight and mildew in its course. If he laughs at the follies of the world, it is not that he has any less love for the good souls who commit them, but that with his exuberant good-nature he has no heart to use a more destructive weapon than his lambent irony. With his fine moral influence, he never affects the sternness of a reformer. He is utterly free from all didactic pedantry. We know nothing that he has written with a view to ethical effect. He reveals his own nature in the sweet flow of his delicate musings, and if he does good it is with delightful unconsciousness. He would blush to find that he had been useful when he aimed only to give pleasure, or rather to relieve his own mind of its "thick coming fancies."

In describing the position of Mr. Irving in the field of American literature, we have incidentally touched upon the characteristics of his genius, to which he is indebted for his high and enviable fame. We need not expand our rapid sketch into a labored analysis. Indeed every just criticism of his writings would only repeat the verdict that has so often been pronounced by the universal voice.

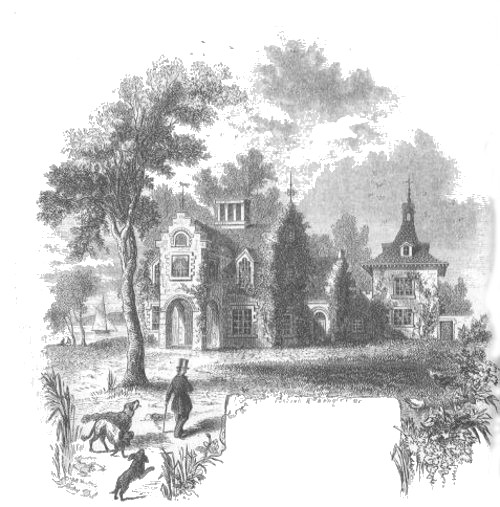

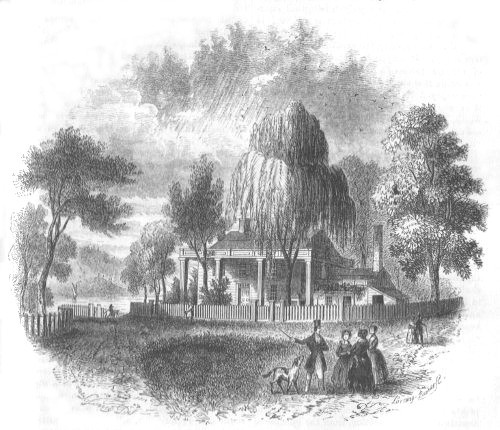

Nor is it exclusively as a writer that Mr. Irving has won such a distinguished place in the admiration of his countrymen. While proud of his successes in the walks of literature, they have regarded his personal character with affectionate delight, and lavished the heartfelt sympathies on the man which are never paid to the mere author. The purity of this offering is the more transparent, as Mr. Irving has never courted the favor of the public, nor been placed in those relations with his fellow-men, that are usually the conditions of general popularity. He has wisely kept himself apart from the excitements of the day; with decided political opinions, he has abstained from every thing like partisanship; no one has been able to count on his advocacy of any special interests; and with his singular fluency and grace of expression in written composition, he has never affected the arts of popular oratory. His habits have been those of the well-educated gentleman—neither cherishing the retirement of the secluded student, nor seeking a prominence in public affairs—throwing a charm over the social circles which he frequented by the brilliancy of his intellect, [Pg 580] the amenity of his manners, and the ease of his colloquial intercourse—but never surrounded by the prestige of factitious distinction by which so many inferior men obtain an ephemeral notoriety. His appointment as Minister to Spain has been his sole official honor; and this was rather a tribute to his literary eminence than the reward of political services. On his return from Europe in 1832, after an absence of nearly twenty years, he was received with a spontaneous welcome by his fellow-citizens, such as has been seldom enjoyed by the most successful claimants of popular favor; and from that time to the present, no one has shown a more undisputed title to the character of the favorite son of Manhattan. In his beautiful retreat at Sunnyside, "as quiet and sheltered a nook as the heart of man could desire in which to take refuge from the cares and troubles of this world," he listens to the echoes of his fame, cheered by the benedictions of troops of friends, and enjoying the autumn maturity of life with no mists of envy and bitterness to cloud the purple splendors of his declining sun.

It is understood that Mr. Irving is now engaged in completing the Life of Washington, a work of which he commenced the preparation before his residence in Europe as Minister to the Spanish Court. We are informed that it will probably be given to the public in the course of another season. It can not fail to prove a volume of national and household interest. The revered features of the Immortal Patriot will assume a still more benignant aspect, under the affectionate and skillful touches of the congenial Artist. With his unrivaled power of individualization, his practiced ability in historical composition, and his acute sense of the moral perspective in character, he will present the illustrious subject of his biography in a manner to increase our admiration of his virtues, and to inspire a fresh enthusiasm for the wise and beneficent principles of which his life was the sublime embodiment. There is a beautiful propriety in the still more intimate connection of the name of Washington Irving with that of the Father of his Country. It is meet that the most permanent and precious memorial of the First Chief of the American Republic should be presented by the Patriarch of American Letters. It would be a fitting close of his bright career before the public—the melodious swan-song of his historic Muse.

The birthplace of Mr. Bryant, in a secluded and romantic spot among the mountains of western Massachusetts, seems to have been selected by Nature as a fit residence for the early unfolding of high poetic genius. Situated on the forest elevations above the beautiful valley of the Connecticut in the old county of Hampshire, surrounded by a rare combination of scenery, in which are impressively blended the wild and rugged with the soft and graceful, adorned in summer with the splendors of a rapid and luxuriant vegetation, in winter exposed to the fiercest storms from the northwest which bury the roads and almost the houses in gigantic snow-drifts, inhabited by a hardy and primitive population which exhibit the peculiar traits of New England character in their most salient form, the little town of Cummington has the distinction of giving birth to the greatest American poet.

It was here that he was first inspired with a sense of the glory and mystery of Nature—first learned to "hold communion with her visible forms," and to lend his ear to her "various language"—first awoke to the consciousness of the "vision and the faculty divine," which he has since displayed in such manifold forms of poetic creation. It was under the shadow of his "native hills"—

"Broad, round, and green, that in the summer sky

With garniture of waving grass and grain,

Orchards, and beechen forests basking lie,

While deep the sunless glens are scooped between

Where brawl o'er shallow beds the streams unseen"—

in the "groves which were God's first temples," where the "sacred influences"

"From the stilly twilight of the place,

And from the gray old trunks, that high in heaven

Mingled their mossy boughs, and from the sound

Of the invisible breath, that swayed at once

All their green tops, stole over him"—

that the spirit of the boy-poet was touched with the mystic harmonies of the universe, and received those impressions of melancholy grandeur from natural objects, which pervade the most characteristic productions of his genius.

Mr. Bryant's vocation for poetry was marked at a very early age. The history of literature scarcely affords an example of such a precocious, and, at the same time, such a healthy development. His first efforts betray no symptoms of a forced, hot-bed culture, but seem the spontaneous growth of a prolific imagination. They are free from the spasmodic forces which indicate a morbid action of the intellect, and flow in the polished, graceful, self-sustaining tranquillity, which is usually the crowning attainment of a large and felicitous experience. Among his earliest productions were several translations [Pg 582] from different Latin poets, some of which, made at ten years of age, were deemed so successful, as to induce his friends to publish them in the newspaper of a neighboring town. These were followed by a regular satirical poem, entitled "The Embargo," written during the heated political controversies concerning the policy of Mr. Jefferson, many of whose most strenuous opponents resided at Northampton (at that time the centre of political and social influence to a wide surrounding country), and from the contagion of whose intelligence and zeal, the susceptible mind of the young poet could not be expected to escape. This was published in Boston, in 1808, before the author had completed his fourteenth year. Its merits were at once acknowledged; it was noticed in the principal literary review of that day; it was read with an eagerness in proportion to the warmth of party spirit; and, indeed, so strong was the impression which it made on the most competent judges, that nothing but the explicit assertions of the friends of the writer could convince them of its genuineness. It seemed, in all respects, too mature and finished a performance to have proceeded from such a juvenile pen. This point, however, was soon decided, and if any remaining doubts lingered in their minds, they might have been removed by the production of "Thanatopsis," which was written about four years after, when the author was in the beginning of his nineteenth year.

This remarkable poem was not published until 1816, when it appeared in the North American Review, then under the charge of Mr. Dana, who has himself since attained to such a signal eminence among the poets and essayists of America, and between whom and Mr. Bryant a singular unity of intellectual tastes laid the foundation for a cordial friendship, which has been maintained with a warmth and constancy in the highest degree honorable to the character of both parties. Meanwhile, Mr. Bryant had established himself in the profession of the law, in the beautiful village of Great Barrington, exchanging the mountain wildness of his native region, for the diversified and singularly lovely scenery of the Housatonic Valley, where he composed the lines "To Green Elver," "Inscription for an entrance to a Wood," "To a Waterfowl," and several of his other smaller poems, which have since hardly been surpassed by himself, and certainly not by any other American writer.

The "Thanatopsis," viewed without reference to the age at which it was produced, is one of the most precious gems of didactic verse in the whole compass of English poetry, but when considered as the composition of a youth of eighteen, it partakes of the character of the marvelous. It is, however, unjust to its rich and solemn beauty to contemplate it in the light of a prodigy. Nor are we often tempted to revert to the singularity of its origin, when we yield our minds to the influence of its grand and impressive images. It seems like one of those majestic products of nature, to which we assign no date, and which suggest no emotion but that of admiration at their glorious harmony.

The objection has been made to the "Thanatopsis," that its consolations in view of death are not drawn directly from the doctrines of religion, and that it in fact makes no express allusion to the Divine Providence, nor to the immortality of the soul. These ideas are so associated in most minds with the subject matter of the poem, that their omission causes a painful sense of incongruity. But the writer was not composing a homily, nor a theological treatise. His imagination was absorbed with the soothing influences of nature under the anticipation of the "last bitter hour." In order to make the contrast more forcible, the poem opens with a cold and dreary picture of the common destiny. Earth claims the body which she has nourished; man is doomed to renounce his individual being and mingle with the elements; kindred with the sluggish clod, his mould is pierced by the roots of the spreading oak. The sun shall no more see him in his daily course, nor shall any traces of his image remain on earth or ocean.

But the universality of this fate relieves the desolation of the prospect. Nature imparts a solace to her favorite child, glides into his darker musings with mild and healing sympathy, and gently counsels him not to look with dread on the mysterious realm, which is the final goal of humanity. No one retires alone to his eternal resting-place. No couch more magnificent could be desired than the mighty sepulchre in which kings and patriarchs have laid down to their last repose. Every thing grand and lovely in nature contributes to the decoration of the great tomb of man. The dead are every where. The sun, the planets, the infinite host of heaven, have shone on the abodes of death through the lapse of ages. The living, who now witness the departure of their companions without heed, will share their destiny. With these kindly admonitions, Nature speaks to the spirit when it shudders at the thought of the stern agony and the narrow house.

The stately movement of the versification, the accumulated grandeur of the imagery, the vein of tender and solemn pathos, and the spirit of cheerful trust at the close, which mark this extraordinary poem, render it more effective, in an ethical point of view, than volumes of exhortation; while, regarded as a work of art, the unity of purpose with which its leading thought is presented under a variety of aspects, gives it a completeness and symmetry which remove the force of the objection to which we have alluded.

In a similar style of majestic thought is the "Forest Hymn," from which we can not refrain from quoting an inimitable passage, descriptive of the alternation between Life and Death in the Universe, which seems to us to open the heart of the mystery with a truthfulness of insight that has found expression in language of unsurpassable energy. [Pg 583]

"My heart is awed within me, when I think

Of the great miracle that still goes on

In silence, round me—the perpetual work

Of thy creation, finish'd, yet renew'd

Forever. Written on thy works, I read

The lesson of thy own eternity.

Lo! all grow old and die—but see, again,

How on the faltering footsteps of decay

Youth presses—ever gay and beautiful youth,

In all its beautiful forms. These lofty trees

Wave not less proudly that their ancestors

Moulder beneath them. O, there is not lost

One of earth's charms: upon her bosom yet,

After the flight of untold centuries,

The freshness of her far beginning lies,

And yet shall lie. Life mocks the idle hate

Of his arch-enemy, Death—yea, seats himself

Upon the tyrant's throne—the sepulchre,

And of the triumphs of his ghastly foe

Makes his own nourishment. For he came forth

From thine own bosom, and shall have no end."

The soft and exquisite beauty of the lines entitled "To a Waterfowl" is appreciated by every reader of taste. They belong to that rare class of poems which, once read, haunt the imagination with a perpetual charm. A more natural expression of true religious feeling than that contained in the closing stanzas, is nowhere to be met with.

"Thou 'rt gone, the abyss of heaven

Hath swallow'd up thy form; yet, on my heart

Deeply hath sunk the lesson thou hast given,

And shall not soon depart.

"He who, from zone to zone,

Guides through the boundless sky thy certain flight,

In the long way that I must tread alone,

Will lead my steps aright."

But we have no space to dwell upon the attractive details of Mr. Bryant's poetry, though it would be a grateful task to pass in review the familiar productions, of which we can weary as little as of the natural landscape. It needs no profound analysis to state their most general characteristics. Bryant's descriptions of nature are no less remarkable for their minute accuracy than for the richness and delicacy of their suggestions in the sphere of sentiment. No one can ever be tempted to accuse him of obtaining his knowledge of nature at second hand. He paints nothing which he has not seen. His images are derived from actual experience. Hence they have the vernal freshness of an orchard in bloom. He is no less familiar with the cheerful tune of brooks in flowery June than with the voices and footfalls of the thronged city. He has watched the maize-leaf and the maple-bough growing greener under the fierce sun of midsummer; the mountain wind has breathed its coolness on his brow; he has gazed at the dark figure of the wild-bird painted on the crimson sky; and listened to the sound of dropping nuts as they broke the solemn stillness of autumn woods. The scenes of nature which he [Pg 584] has loved and wooed have rewarded him with their beautiful revelations in the moral world. Her dim symbolism has become transparent to the anointed eye of the reverent bard, and initiated him into the mysteries which give a new significance to the material creation.

It is true that the staple of his poetry is reflection, rather than passion, reminding us of the chaste severity of sculpture, and not appealing to the fancy by any sensuous or voluptuous arts of coloring. But a deep sentiment underlies the expression; and he touches the springs of emotion with a powerful hand, though he never ceases to be master of his own feelings. The apparent coldness of which some have complained, may be ascribed to the frigidity of the reader, with more truth than to the apathy of the writer. With its highly intellectual character, the poetry of Mr. Bryant is adapted to win a more profound and lasting admiration than if it were merely the creation of a productive fancy. It may gain a more limited circle of readers (although its universal popularity sets aside this supposition), but they who have once enjoyed its substantial reality will place it on the same shelf with Milton and Wordsworth, with a "sober certainty" that they will always find it instinct with a fresh and genuine vitality.

The influence of this poetry is of a pure and ennobling character; never ministering to false or unhealthy sensibility, it refreshes the better feelings of our nature; inspiring a tranquil confidence in the on-goings of the Universe, with whose most beautiful manifestations we are brought into such intimate communion. Its most pensive tones, which murmur such sweet, sad music, never lull the soul in the repose of despair, but inspire it with a cheerful hope in the issues of the future. The "inexorable Past" shall yet yield the treasures which are hidden in its mysterious depths, and every thing good and fair be renewed in "the glory and the beauty of its prime."

"All shall come back, each tie

Of pure affection shall be knit again;

Alone shall Evil die,

And Sorrow dwell a prisoner in thy reign."

As a prose writer, Mr. Bryant is distinguished for signal excellencies both of thought and expression, evincing a remarkable skill in various departments of composition, from the ephemeral political essay to the high-wrought fictitious tale, and graphic recollections of foreign travel. The superior brightness of his poetic fame can alone prevent him from being known to posterity as a vigorous and graceful master of prose, surpassed by few writers of the present day.

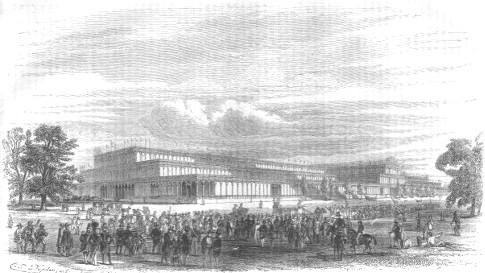

In the early months of last year the Great Exhibition had become as nearly a "fixed fact" as any thing in the future can be. The place where and the building in which it was to be held, then became matters for grave consideration. The first point, fortunately, presented little difficulty, the south side of Hyde-park, between Kensington-road and Rotten-row, having been early selected as the locality.

The construction of the edifice, however, presented difficulties not so easily surmounted. The Building Committee, comprising some of the leading architects and engineers of the kingdom, among whom are Mr. Barry, the architect of the new Houses of Parliament, and Mr. Stephenson, the constructor of the Britannia Tubular Bridge, advertised for plans to be presented for the building. When the committee met, they found no want of designs; their table was loaded with them, to the number of 240. Their first task was to select those which were positively worthless, and throw them aside. By this process the number for consideration was reduced to about sixty; and from these the committee proceeded to concoct a design, which pleased nobody—themselves least of all. However, the plan, such as it was, was decided upon, and advertisements were issued for tenders for its construction. This was the signal for a fierce onslaught upon the proceedings of the committee. For the erection of a building which was to be used for only a few months, more materials were to be thrown into one of the main lungs of the metropolis, than were contained in the eternal pyramids of Egypt. Moreover, could the requisite number of miles of brickwork be constructed within the few weeks of time allotted? and was it not impossible that this should, in so short a time, become sufficiently consolidated to sustain the weight of the immense iron dome which, according to the design of the committee, was to rest upon it?

The committee, fortunately, were not compelled to answer these and a multitude of similar puzzling interrogatories which were poured in upon them. Relief was coming to them from an unexpected quarter: whence, we must go back a little to explain.

On New Year's Day, of the year 1839, Sir Robert Schomburgk, the botanist, was proceeding in a native boat up the River Berbice, in Demerara. In a sheltered reach of the stream, he discovered resting upon the still waters an aquatic plant, a species of lily, but of a gigantic size, and of a shape hitherto unknown. Seeds of this plant, to which was given the name of "Victoria Regia," were transmitted to England, and were ultimately committed to the charge of Joseph Paxton, the horticulturist at Chatsworth, the magnificent seat of the Duke of Devonshire. The plant produced from these seeds became the occasion, and in certain respects the model, for the Crystal Palace.

Every means was adopted to place the plant in its accustomed circumstances. A tropical soil was formed for it of burned loam and peat; Newcastle coal was substituted for a meridian sun, to produce an artificial South America under an English heaven; by means of a wheel a ripple like that of its native river, was communicated to the waters of the tank upon which [Pg 585] [Pg 586] its broad leaves reposed. Amid such enticements the lily could not do otherwise than flourish; and in a month it had outgrown its habitation. The problem was therefore set before its foster-father to provide for it, within a few weeks, a new home. This was not altogether a new task for Mr. Paxton, who had already devoted much attention to the erection of green-houses; and within the required space of time, he had completed this house for the "Victoria Regia," and therein, in the sense in which the acorn includes the oak, that of the Crystal Palace.

While Mr. Paxton was planning an abode for this Brobdignagian lily, the Building Committee of the Exhibition were poring wearily over the 240 plans lying upon their table. They had rejected the 180 worthless ones, and from the remainder had concocted, as we have said, with much cogitation and little satisfaction, their own design. Such as it was, however, it was determined that it should be executed—if possible.

This brings us down to the middle, or to be precise, to the 18th of June, on which day Mr. Paxton was sitting as chairman on a railway committee. He had previously made himself acquainted with the case laid before them, and was not therefore under the necessity of now devoting his attention to it. He took advantage of this leisure moment to work out a design for the Exhibition Building, which he had conceived some days previously. In ten days thereafter elevations, sections, working plans and specifications, were completed from this draft, and the whole was submitted to the inspection of competent and influential persons, by whom it was unanimously announced to be practicable, and the only practicable scheme presented.

This design was then laid before the contractors, Messrs. Fox and Henderson, who at once determined to submit a tender for the construction of a building in accordance with it. In a single week, they had calculated the amount and cost of every pound of iron, every pane of glass, every foot of wood, and every hour of labor which would be required, and were prepared with a tender and specifications for the construction of the edifice. But here arose a difficulty. The committee had advertised only for proposals for carrying out their own design; but, fortunately, they had invited the suggestion on the part of contractors, of any improvements upon it; and so Mr. Paxton's plan was presented simply as an "improvement" upon that of the committee, with which it had not a single feature in common. This, with certain modifications, was adopted, and the result is the Crystal Palace—itself the greatest wonder which the Exhibition will present—the exterior of which is represented in our accompanying Illustration.

The building consists of three series of elevations of the respective heights of 64, 44, and 24 feet, intersected at the centre by a transept of 72 feet in width, having a semicircular roof rising to the height of 108 feet in the centre. It extends in length 1851 feet from north to south, more than one-third of a mile, with a breadth of 456 feet upon the ground; covering 18 superficial acres, nearly double the extent of our own Washington-square; and exceeding by more than one half the dimensions of the Park or the Battery. The whole rests upon cast-iron pillars, united by bolts and nuts, fixed to flanges turned perfectly true, so that if the socket be placed level, the columns and connecting-pieces must stand upright; and, in point of fact, not a crooked line is discoverable in the combination of such an immense number of pieces. For the support of the columns, holes are dug in the ground, in which is placed a bed of concrete, and upon this rest iron sockets of from three to four feet in length, according to the level of the ground, to which the columns are firmly attached by bolts and nuts. At the top, each column is attached by a girder to its opposite column, both longitudinally and transversely, so that the whole eighteen acres of pillars is securely framed together.

The roofs, of which there are five, one to each of the elevations, are constructed on the "ridge and furrow" principle, and glazed with sheets of glass of 49 inches in length. The construction will be at once understood by imagining a series of parallel rows of the letter V (thus, \/\/\/), extending in uninterrupted lines the whole length of the building. The apex of each ridge is formed by a wooden sash-bar with notches upon each side for holding the laths in which are fitted the edges of the glass. The bottom bar, or rafter, is hollowed at the top so as to form a gutter to carry off the water, which passes through transverse gutters into the iron columns, which are hollow, thus serving as water-pipes; in the base of the columns horizontal pipes are inserted, which convey the accumulated water into the sewers. The exhalations, from so large an extent of surface, from the plants, and from the breath of the innumerable visitors, rising and condensed against the glass, would descend from a flat roof in the form of a perpetual mist, but it is found that from glass pitched at a particular angle the moisture does not fall, but glides down its surface. The bottom bars are therefore grooved on the inside, thus forming interior gutters, by which the moisture also finds its way down the interior of the columns, through the drainage pipes, into the sewers. These grooved rafters, of which the total length is 205 miles, are formed by machinery, at a single operation.

The lower tier of the building is boarded, the walls of the upper portion being composed, like the roof, of glass. Ventilation is provided for by the basement portion being walled with iron plates, placed at an angle of 45 degrees, known as luffer-boarding, which admits the air freely, while it excludes the rain. A similar provision is made at the top of each tier of the building. These are so constructed that they can be closed at pleasure. In order to subdue the intense [Pg 587] light in a building having such an extent of glass surface, the whole roof and the south side will be covered with canvas, which will also preclude the possibility of injury from hail, as well as render the edifice much cooler.

In the construction of the building care has been taken to give to each part the stiffest and strongest form possible in a given quantity of material. The columns are hollow, and the girders which unite them are trellis-formed. The utmost weight which any girder will ever be likely to sustain is seven and a half tons; and not one is used until after having been tested to the extent of 15 tons; while the breaking weight is calculated at 30 tons. At first sight, there would seem to be danger that a building presenting so great a surface to the action of the wind, would be liable to be blown down. But from the manner in which the columns are framed together they can not be overthrown except by breaking them. Experiments show that in order to break the 1060 columns on the ground floor, a force of 6360 tons must be exerted, at a height of 24 feet. The greatest force of the wind ever known is computed at 22 pounds to the superficial foot; assuming a possible force of 28 pounds, and suppose a hurricane of that momentum to strike at once the whole side of the building, the total force would be less than 1500 tons—not one-fourth of the capacity of the building to sustain, independent of the bracings, which add materially to its strength. So that, if any reliance at all can be placed upon theoretical engineering, there can be no doubt as to the safety of the building.

Entering at the main east or west entrance, we find ourselves in a nave 64 feet in height, 72 in breadth, and extending without interruption the whole length of the building, one-third of a mile. Parallel with this, but interrupted by the transept in the centre, are a series of side aisles of 48 and 24 feet in breadth, with a height of 44 and 24 feet. Over the centre of the nave swells the semicircular roof of the transept, overarching the stately trees beneath—a Brobdignagian green-house with ancient elms instead of geraniums and rose-bushes. The whole area of the ground floor is 772,784 square feet; and that of the galleries 217,100; making in all within a fraction of one million square feet; to which may be added 500,000 feet of hanging-space, available for the display of the products of human heads and hands.

There are three refreshment rooms, one in the transept, and one near each end, around the trees which were left standing, where ices and pastry for the wealthy, and bread-and-butter and cheese for the poorer are to be furnished. No wine, spirits, or fermented liquors are to be sold; only tea, coffee, and unfermented drinks; pure water is to be furnished gratis to all comers by the lessees of the refreshment rooms.

In respect to the decoration of the interior, a keen controversy has been waged. The fact of iron being the material of construction renders it necessary that it should be painted to preserve it from the action of the atmosphere. On the one hand, it is said that the fact that the structure is metallic should be indicated by the decoration, otherwise the whole will have no more appearance of stability than an arbor of wicker-work. Those who take this view recommend that the interior should be bronzed. On the other hand, those to whom the decoration is intrusted affirm that the object of using color is to increase the effect of light and shade. If the whole were of one uniform dead color the effect of the innumerable parts of which the building is composed, all falling in similar lines, one before the other, would be precisely that of a plane surface; the extended lines of pillars presenting the aspect of a continuous wall. In order to bring out the distinctive features of the building various colors must be used; and experiments show that a combination of the primary colors, red, blue, and yellow, is most pleasant to the eye. The best means for using these is to place blue, which retreats, upon the concave surfaces, yellow, which advances, upon the convex ones, reserving red for plane surfaces. But as when these colors come in contact each becomes tinged with the complementary color of the other—the blue with green, the red with orange—a line of white is interposed between them. Applying these principles, the shafts of the columns are to be yellow, the concave portions of their capitals blue, the under side of the girders red, and their vertical surfaces white.

Among all the wonders of the Crystal Palace nothing is more wonderful than its cheapness, and the rapidity of its construction. Possession of the site was obtained on the 30th of July; in a period of only 145 working-days the building was to all intents and purposes completed. As to cheapness it costs less per cubic foot than an ordinary barn. If used only for the Exhibition, and at its close returned to the contractors, the cost will be nine-sixteenths of a penny a foot; or, if permanently purchased, it will be one penny and one-twelfth. Thus: The solid contents are 33,000,000 cubic feet; the price if returned is £79,800, if retained £150,000. This simple fact, that a building of glass and iron, covering eighteen acres, affording room for nine miles of tables, should have been completed in less than five months from the day when the contract was entered into, at a cost less than that of the humblest hovel, opens a new era in the science of building.

As to the final destination of the Crystal Palace, it is the wish of the designer that it should be converted into a permanent winter-garden with drives and promenades. Leaving ample space for plants, there would be two miles of walks in the galleries, and the same amount for walks upon the ground floor; in summer the removal of the upright glass would give the whole the appearance of a continuous walk or garden. [Pg 588]

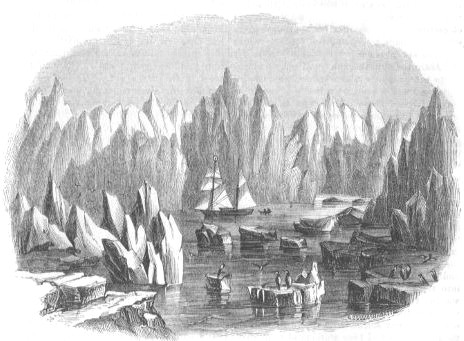

Sir John Franklin, in command of the "Erebus" and "Terror," having on board one hundred and thirty-eight souls, set sail from England on the 19th of May, 1845, in search of a northwest passage. On the 26th of July, sixty-eight days afterward, they were seen by a passing whaler moored to an iceberg near the centre of Baffin's Bay; since which time no intelligence of their fate has been received. No special anxiety was entertained respecting them until the beginning of 1848, for the commander had intimated that the voyage would probably continue for three years, and that they might be the first to announce their own return. But as month after month passed away without bringing any tidings, an anxious and painful sympathy sprung up in the public mind, and the British Government determined that searches for the missing vessels should be made in three different quarters by three separate expeditions fitted out for that purpose.

One quarter, however, that region known as Boothia, where there was a probability of success, was beyond the scope of these expeditions, and Lady Franklin determined to organize an expedition to explore that region. For this purpose she appropriated all the means under her control; and a subscription was opened to supply the deficiency. The "Prince Albert," a ketch of less than ninety tons burden, measuring in length about seventy-two feet, and seventeen in breadth, was purchased for the expedition. She was taken to Aberdeen to be fitted up; a double planking was put upon her, by way of pea-jacket to fit her for her arctic voyage, and a crew of fourteen canny Scotchmen, secured by the promise of double pay. Captain Forsyth, of the Royal Navy, proffered his gratuitous services as commander. Attached to the expedition, having special charge of the stores and scientific instruments, with the express understanding that he should head one of the exploring parties to be sent out from Regent's Inlet, was Mr. W. Parker Snow, from whose Journal we propose to draw up some account of the pleasures of sailing through the ice.

Mr. Snow seems to have been precisely the man for such an undertaking. He left America at three days' notice to join any expedition which might be sent out by Lady Franklin. With an active, hopeful temperament, never so happy as in a gale of wind, if it was only blowing the right way, he rushed to the embrace of the Arctic Snows with as much alacrity as though they were kinsmen as well as namesakes. He had, moreover, a happy faculty of turning his hand to every thing, and no disposition to hide his talent in a napkin. A physician had been engaged for the vessel; but when, two days before sailing, the disciple of Esculapius saw the diminutive craft, he declined to proceed:—Mr. Snow volunteered to perform his duties; he had read a little medicine at odd [Pg 589] hours; and by the aid of Rees's Guide, and Smee's Broadsheet, his practice was uniformly successful—either in spite of, or on account of, his informal professional training. The sailors, as might be expected from their Scotch blood, were desirous of having religious worship on board:—Mr. Snow offered his services as chaplain, reading and expounding the Scriptures, and offering up prayer.

On the 6th of June, 1850, the Prince Albert set sail from Aberdeen; a fortnight brought them within two hundred miles of the shores of Greenland. Then came, for a week, a succession of heavy gales, which drove them back upon their course; so that in six days their progress was not more than a dozen miles. The 1st of July, however, found them off Cape Farewell. Some idea of the multifarious occupations of the many-officed Mr. Snow, at a time when his proper duties had not commenced, may be gathered from his description of

"At half-past six I used to turn out; and, warm or cold, wet or dry, take an immediate ablution in the pure and natural element. For half an hour I would then walk on deck, fair or foul; and, a little before eight, examine the men's forecastle; see to their condition, and whether any of them were sick; and if so, give them medicine. At eight bells, I would then take the chronometrical time for Captain Forsyth, while he observed the altitude of the sun, to get our longitude. Latterly I used, by his desire, to take a set of sights also myself, taking the time from a common watch, and comparing it afterward with the chronometer. The chronometers were then wound up by me, and the thermometer, barometer, &c., registered. At eight o'clock the two mates went to breakfast; the captain and I getting ours soon after them. During the forenoon I had to attend to the stores, provisions, &c.; write my accounts, journals, and other papers; and at noon worked up the ship's reckoning, the observations, and wrote the ship's log, examining our present position and future course. The mates had their dinner at noon: the captain and I at three P.M.; after which, a stroll for an hour or so on deck was taken by both of us. Tea came round at six, and at eight P.M. I used to try the temperature of the air on deck, and of the sea. After that, we would read together in the stern cabin. At ten, we would take our hot grog; and, generally about eleven, when free from rough weather or the neighborhood of ice, turn in for the night. Very little candle was required below at night, as there was seldom more than an hour or two's darkness during any part of our voyage, until we were returning. It was not long after this date, moreover, that we had continued daylight through the whole twenty-four hours."

The principal obstruction and danger in arctic navigation arises from the ice; fields of which often occur of twenty or thirty miles in diameter, and ten or fifteen feet in thickness. From these crystal plains rise sometimes isolated, sometimes in groups, elevations of thirty or more feet in height, called hummocks. Dr. Scoresby once saw a field so free from hummocks and fissures that a coach might have traversed it for leagues in a straight direction, without obstruction. In May or June these fields begin to drift along in solemn procession to the southwestward, in which direction they hold their steady course, whether in calm or in spite of adverse winds. When these floating continents emerge from the drift ice which had hitherto protected them, they are shattered and broken up by the long, deep swell of the ocean. A ground-swell, hardly perceptible in the open sea, will break up a field in a few hours. These fields sometimes acquire a rotary motion, which gives their circumference a velocity of several miles an hour, producing a tremendous shock when one impinges upon another. "A body of more than ten thousand millions of tons in weight," says Dr. Scoresby, "meeting with resistance when in motion, produces consequences scarcely possible to conceive. The strongest ship is but an insignificant impediment between two fields in motion."—Mr. Snow gives the following account of

"We had come so quickly and unexpectedly upon this "stream" (not having seen it, owing to the thick weather, until close aboard of it), that promptitude of decision and movement was absolutely necessary. It was one of those moments when the seaman comes forward, and by boldly acting, either in the one way or the other, shows what he is made of. In the present case the question instantly arose as to whether the vessel should at once run through the ice now before her, or wait until clearer and milder weather came. The mate, as ice-master, was asked by the captain which, in his opinion, was best. He advised heaving to, to windward of it, and waiting. The second mate was then asked; and he, without knowing the other's opinion, strongly urged the necessity of running through at once. Captain Forsyth, using his own judgment, very wisely decided upon the latter, and accordingly run the ship on. And a pretty sight, too, it was, as the "Prince Albert" under easy and working sail, in a moment or two more entered the intricate channels that were presented to her between numerous bergs and pieces of ice, rough and smooth, large and small, new and old, dark and white. It was hazy weather, snowing and raining at the time; and all hands having been summoned on deck, were wrapped in their oil-skin dresses and waterproof overcoats. Standing on the topsail-yard was the second mate conning the ship; half-way up the weather rigging clung the captain, watching and directing as necessary; while aft, on the raised counter near the wheel, stood the chief mate telling the helmsman how to steer. This being the first ice in any large and continuous quantity that we had met, I looked at it with some curiosity. The moment we had entered within the outer edge of the stream the water became as smooth as a common [Pg 590] pond on shore; and it was positively a pretty sight to see that little vessel dodging in and out and threading her way among the numerous pieces of ice that beset her proper and direct course. The ice itself presented a most beautiful appearance both in color and form, being variegated in every direction. We were soon in the very thick of it; and before five minutes had elapsed from our first taking it we could see no apparent means of either going on or retracing our steps. But it was well managed, and after about an hour's turning hither and thither, this way and that way, straight and crooked, we got fairly through, and found clear water beyond.

"Throughout the night the wind blew a complete hurricane, and the short high sea was perfectly furious; lashing about in all directions with the madness of a maelström, and with a violence that, apparently, nothing could resist. Heavy squalls, with sharp sleet and snowstorms from the southward, added to the fearful tempest that was raging. It was impossible to see three miles ahead, the weather being so thick. Occasionally an iceberg would dart out through the mist, heaving its huge body up and down in frightful motion, now advancing, next receding, and again approaching with any thing but pleasant proximity. Our little vessel, however, as usual, stood it well. Could we have divested ourselves of the reality of the scene, it might have been likened to a fancy picture, in which some strange and curious dance was being represented between the sea, the ice, and the ship; the latter, by the aid of the former, gallantly lifting herself to, and then declining from the other. But it was too real; and the greater danger of the land being possibly near, was too strongly impressed upon our minds, to allow any visionary feeling to possess us at the time. It was the worst and most dangerous night we had yet had, and hardly a man on board rested quietly below until the height of it was past."

Soon after this a boat's crew was sent ashore for water, where in a lonely spot they discovered the grave of an European, with an inscription on a rude wooden tablet at its head, stating that "John Huntley of Shetland, was buried there in August, 1847." The sailors replaced the board which had blown down; and left the solitary grave, with the humble tribute of a wish for the repose of the poor fellow's soul. A few days later while on shore, Mr. Snow was spectator of the

"I was speedily awakened to reality by a sudden noise like the cracking of some mighty edifice of stone, or the bursting of several pieces of ordnance. Ere the sound of that noise had vibrated on the air, a succession of reports like the continued discharge of a heavy fire of musketry, interspersed with the occasional roar of cannon, followed quickly upon one another, for the space of perhaps two minutes; when, suddenly, my eye was arrested by the oscillation of a moderate-sized iceberg not far beneath my feet, in a line away from the hill I was upon; and the next moment it tottered, and with a sidelong inclination, cut its way into the bosom of the sea upon which it had before been reclining. Roar upon roar pealed in echoes from the mountain heights on every side: the wild seabird arose with fluttering wings and rapid flight as it proceeded to a quarter where its quiet would be less disturbed: the heretofore peaceful water presented the appearance of a troubled ocean after a fierce gale of wind; and, amid the varied sounds now heard, human voices from the boat came rising up on high in honest English—strangely striking on the ear—hailing to know if I had seen the 'turn,' and also whether I wanted them to join me. But an instant had not passed before the mighty mass of snow and ice which had so suddenly overturned, again presented itself above the water. This time, however, it bore a different shape. The conical and rotten surface that had been uppermost, when I had first noticed it, was gone, and a smooth, table-like plane, from which streamed numerous cascades and jets d'eau, was now visible. The former had sunk some hundred feet below, when the 'berg,' reversing itself, had been overturned by its extreme upper weight, and thus brought the bottom of it high above the level of the sea."

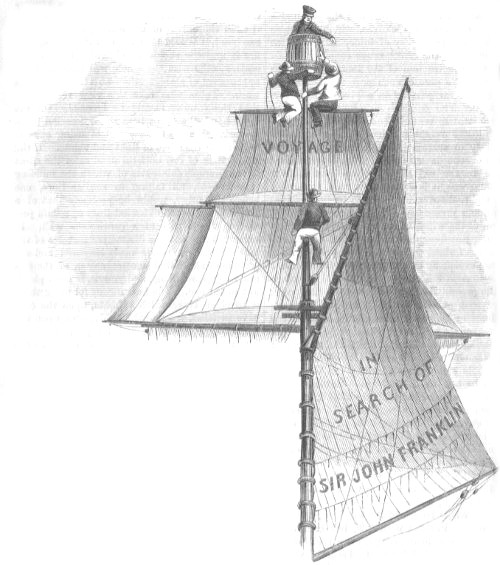

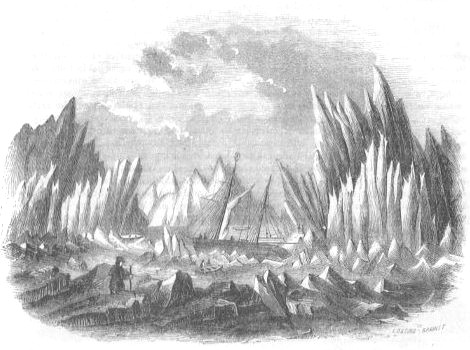

Northward, and still northward: thicker and more continuous grew the ice-plains, while ever and anon a sound like the discharge of heavy artillery booming along the lonely seas, announced that one iceberg after another had burst amid this freezing arctic midsummer. They now found that they were approaching the great Pack, where their labors were properly to begin. Due preparations were made, by laying in order ice-anchors, claws, and axes, getting tow-ropes, warps, and tracking-belts in order for instant use, and

"The 'Crow's Nest' is a light cask, or any similar object, appointed for the look-out man aloft to shelter himself in, and is in large ships generally at the topmast head. In smaller vessels, however, it is necessary to have it as high up as possible, in order to give from it a greater scope of vision than could be attained lower down. Consequently, in the Prince Albert it was close to the 'fore-truck,' that is, completely at the mast-head. In our case, it was a long, narrow, but light cask, having at the lower part of it a trap, acting like a valve, whereby any one could enter; and was open at the upper part. In length it was about four feet, so that a person on the look-out had no part of himself exposed to the weather but his head and shoulders. In the interior of it was a small seat, slung to the hinder part of the cask, and a spyglass, well secured. To reach this, a rope ladder was affixed to the bottom of it, as seen in the engraving. This is called the 'Jacob's Ladder,' and the boatswain may be observed attaching the lower parts of it to the foremast-head. [Pg 591] Upon the top-gallant yard are two men, busy in securing the cask to the mast, while the second mate is inside trying its strength, and giving directions concerning it. The 'Crow's Nest' is a favorite place with many whaling captains, who are rarely out of it for days when among the ice. I was very frequently in it myself, fair weather or foul—from six to a dozen times a day—both for personal gratification, and for the purpose of looking out. It was a favorite spot with me at midnight, when the atmosphere was clear, and the whole beauty of arctic scenery was exposed to view. It was all fresh to me: I enjoyed it; and had enough to do, admiring the enormous masses of ice we were passing, the white-topped mountains in the distance, and the strange aspect of every thing around me. It seemed, as we slowly threaded our way through the bergs, that we were about approaching some great battle-field, in which we were to be actively engaged; and that we were now, cautiously, passing through the various outposts of the mighty encampment; at other times I could almost fancy we were about to enter secretly, by the suburbs, some of those vast and wonderful cities whose magnificent ruins throw into utter insignificance all the grandeur of succeeding ages. Silently, and apparently without motion, did we glide along, amidst dark hazy weather, rain, and enough wind to fill the sails and steady them, but no more."

Northward yet, and ever northward:—More frequent and massive grew the icebergs among which the little "Prince Albert" threaded its way; while far and near, to the east and north and west the eye met nothing but a uniform dazzling whiteness shot up from the glittering ice-peaks. Now and then a bear was seen, sitting a grim sentinel, by some seal-hole, from which his prey was soon "expected out." As they advanced the ice closed in around them, until at last they were fairly

"We were fairly 'in the ice:' but ice of which most readers have no idea. The water frozen in our ponds and lakes at home is but as a mere thin pane of glass in comparison to that which now came upon us. Fancy before you miles and miles of a tabular icy rock eight feet or more, solid, thick throughout, unbroken, or only by a single rent here and there, not sufficient to separate the piece itself. Conceive this icy rock to be in many parts of a perfectly even surface, but in others covered with what might well be conceived as the ruins of a mighty city suddenly destroyed by an earthquake, and the remains jumbled together in one confused mass. Let there be also huge blocks of most fantastic form scattered about upon this tabular surface, and in some places rising in towering height, and in one apparently connected chain, far, far beyond the sight. Take these in your view, and you will have some faint idea of what was the kind of ice presented to my eye as I gazed upon it from aloft. We had at last come to the part most dreaded by the daring and adventurous whalers. Melville's Bay, often called, from its fearful character, the 'Devil's Nip,' was opening to my view, and stretching away far to the northward out of sight. But neither bay nor aught else, except by knowledge of its position, could I discover. Every where was ice; and the wonder to me was, how we were to get [Pg 592] on at all through such an apparently insurmountable barrier.

"Our position now was becoming more and more confined as to sailing room. The channel in which we had hitherto been quietly gliding, narrowed till little better than the breadth of the ship. At 4h 30m P.M. we could get no further, a barrier of 'hummocky' ice intervening right across our passage between us and some open water, visible not above seventy yards from us. Speedily the channel through which we had come began to close, and after trying in vain to force our way through the obstruction, we found ourselves at six o'clock completely beset. The Devil's Thumb, which was now plainly visible, at this time bore S.E. (compass) about thirty miles. Other land was also seen topping over enormous glaciers, which were most wonderful to look at, and used to entrance my gaze for hours. At six o'clock our actual labors in the ice commenced. It was beginning to press upon us rather hard; and from the appearance of that which blocked our way, it was evident there had been a heavy squeeze here, and we were afraid of getting fixed in another. Accordingly every effort was made to remove the obstacle which impeded our passage. We first began to try and heave the ship through by attaching strong warps to ice anchors, which latter being fastened in the solid floe, enabled a heavy strain to be put in force. The windlass was then set to work, but to no purpose, as we hardly gained a fathom. We next tried what heaving out the pieces that were in our way would do, but this proved of no avail. The saws were then set to work to cut off some angular projections that inconveniently pressed against our side; and while this was being done, I sprung on to the hummocky pieces and examined the difficulty. The obstacle, however, was not removed; and at two in the morning a crack in the large floe to the westward of us was observed to be gradually enlarging. In less than half an hour the water appeared in larger quantities astern, and a 'lane' was opened, by a circuitous route, into the clear space ahead of us, whither we wanted to go. All hands were called to the ship, and the vessel's head turned round to the southward, any further attempt to get through the channel we had been working at being given up. Sail was made to a light breeze, and some delicate manœuvring had to be accomplished in getting the ship round and in among some heavy ice, toward the passage we wished to enter.

"When I went on deck the next morning about eight, I found the weather very thick, with heavy rain. Our position seemed to me but little improved from that of the past night, for numerous 'bergs' of every size and shape appeared to obstruct our path. A fresh breeze was blowing from the S.E., and our ship was bounding nimbly to it in water as smooth as a mill-pond. But no sooner did she get to the end of her course one way, than she had to retrace her steps and try it another. We seemed completely hemmed in on every side by heavy packed ice, rough uneven hummocks, or a complete fleet of enormous bergs. Like a frightened hare did the poor thing seem to fly, here, there, and every where, vainly striving to escape from the apparent trap she had got into. It was a strange and novel sight. For three or four hours—indeed ever since we had entered this basin of water, we had been vainly striving to find some passage out of it, in as near a direction as possible to our proper course, but neither this way, nor any other way, nor even that in which we had entered (for the passage had again suddenly closed), could we find one. At last, about ten A.M., an opening between two large bergs was discovered to the N.W. Without a moment's delay our gallant little bark was pushed into it, and soon we found ourselves threading through a complete labyrinth of ice rocks, if they may be so called, where the very smallest of them, ay, or even a fragment from one of them, if falling on us, would have splintered into ten thousand pieces the gallant vessel that had thus thrust herself among them, and would have buried her crew irretrievably. Wonderful indeed was it all. Numerous lanes and channels, not unlike the paths and streets of a mighty city, branched off in several directions; but our course was in those that led us most to the northward. Onward we pursued our way in this manner for about two hours, when, suddenly, on turning out of a passage between some lofty bergs, we found the view opening to us, a field of ice appearing at the termination of the channel, and at the extreme end a schooner fast to a 'floe,' that is, lying alongside the flat ice, as by a quay. The wind was fair for us, blowing a moderate breeze, so that we soon ran down to her in saucy style, rounding to just ahead of her position, and making fast in like manner. To our great joy we found that, as we had suspected, and, indeed, knew, as soon as colors were hoisted, it was indeed Sir John Ross in the 'Felix.' Glad was I of an opportunity to see the gallant old veteran, whose name and writings had latterly been so frequently before me. Directly we got on board, Sir John Ross came to meet us; I saw before me him who, for four long years and more, had been incarcerated, hopelessly, with his companions, in those icy regions to which we ourselves were bound. I was struck with astonishment! It was nothing, in comparison, for the young and robust to come on such a voyage; but that he, at his time of life, when men generally think it right—and right, perhaps, it is, too—to sit quietly down at home by their own firesides, should brave the hardship and danger once again, was indeed surprising.

"In the evening both vessels had to move into another position, in consequence of the bergs approaching too closely toward us. To watch these mountain, icy monsters in a calm, as they slowly and silently, yet surely and determinedly, move about in the narrow sheet of water by which they chance to be encompassed, one could well imagine that it was some huge mysterious [Pg 593] thing, possessed of life, and bent on the fell purpose of destruction. Onward it almost imperceptibly glides, until reaching an opposing floe, it forces its way far through the solid ice, plowing up the pieces and throwing them aside in hilly heaps with a force and power apparently incredible. Should it happen that an impetus is given to it by wind, or other causes besides those thus occasioned by the tide, or current, it is mighty in its strength, and terrific in the desolation it produces. Nothing can save a ship if thus caught by one, as was the case in the memorable and fatal year of 1830, in this very bay, when vessels were 'squeezed flat'—'reared up by the ice, almost in the position of a rearing horse! others thrown fairly over on their broadsides; and some actually overrun by the advancing floe and totally buried by it.'"

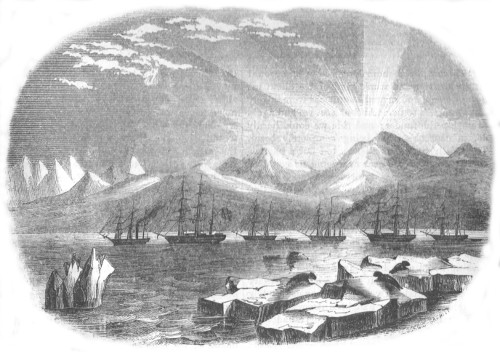

The obstructions presented by the ice continued to increase so that in a whole fortnight, in spite of the most strenuous exertions, they made only twelve miles in their northward course. And even this, as they subsequently learned, was more than was performed by the government expedition, which was five weeks in advancing thirty miles. On the third of August, in Melville's Bay, night closed in upon

"There was still more danger now, on account of the heavier and worse kind of ice about us. Several bergs and rugged hummocks were in very close quarters to us. At four A.M. we had again to unship the rudder; and this we could hardly do, in consequence of being completely beset. The 'Felix,' was just ahead; but not a particle of water any where near or around us could be seen. Several times both vessels were in extreme danger; and once we sustained a rather heavy pressure, being canted over on the starboard side most unpleasantly. But the 'Prince Albert' stood it well; although it was painfully evident that should the heavy outer floes still keep setting in upon those which inclosed us, nothing could save her. To describe our position at this moment it will be only necessary to observe that both vessels were as completely in the ice as if they had been dropped into it from on high, and frozen there. It had been impossible for me to sleep during the night in consequence of the constant harsh grating sound that the floes caused as they slowly and heavily moved along or upon the ship's side, crushing their outer edges with a most unpleasant noise close to my ear. My sleeping berth was half under and half above the level of the water, when the ship was on an even keel. In the morning I heard the grating sound still stronger and close to me: I threw myself off the bed and went on deck. From the deck, I jumped on to the ice, and had a look how it was serving the poor little vessel. Under her stern I perceived large masses crushed up in a frightful manner, and with terrific force, sufficient, I thought, to have knocked her whole counter in. My only wonder was how she stood it; but an explanation, independent of her own good strength, was soon presented to me in the fact that the floe I was standing upon was moving right round, and grinding in its progress all lesser pieces in its way. This was the cause of safety to ourselves and the 'Felix.' Had the heavy bodies of ice been impelled directly toward us, [Pg 594] as we at first feared they would be, instead of passing us in an angular direction, we should both, most assuredly, have been crushed like an egg-shell. The very bergs, or the floating ones, near which we had been fast on the previous day, were aiding in the impetus given by the tide or current to the masses now in motion; and most providential was it that no wind was blowing from the adverse quarter at the time, upon each side of the ship the floes were solid and of great thickness, and pressing closely upon her timbers. Under the bow, several rough pieces had been thrown up nearly as high as the level of the bowsprit, and these were in constant change, as the larger masses drove by them.

"I ascended on deck, and found all the preparations for taking to the ice, if necessary, renewed. Spirits of wine, for portable fuel, had been drawn off, and placed handy; bags of bread, pemmican, &c., were all in readiness; and nothing was wanting in the event of a too heavy squeeze coming. We could perceive that, sooner or later, a collision between the two floes, the one on our larboard and the other on our starboard side, must take place, as the former had not nearly so much motion as the latter; but where this collision would occur was impossible to say. Between the 'Felix' and us, the passage was blocked principally by the same sort of pieces that I have mentioned as lying under our bow; and astern of us were several small bergs that might or might not be of service in breaking the collision. Very fortunately they proved the former; for, presently, I could perceive the floe on our starboard hand, as it came flushing and grinding all near it, in its circular movement, catch one of its extreme corners on a large block of ice a short distance astern, and by the force of the pressure drive it into the opposite floe, rending and tearing all before it; while at the same time itself rebounded, as it were, or swerved on one side, and glided more softly and with a relaxed pressure past us. This was the last trial of the kind our little 'Prince' had to endure; for afterward a gradual slackening of the whole body of ice took place, and at ten it opened to the southward. We immediately shipped the rudder, and began heaving, warping, and tracking the ship through the loose masses that lay in that, the only direction for us now to pursue, if we wished to get clear at all."

On the 10th of August, as the sun, which now never sank below the horizon, rose above a low-lying fog-bank; one of the government expeditions was seen emerging from the mist. The expedition consisted of two screw steamers, each having a sailing vessel in tow. A strange sight it was to see these steamers—the first that ever burst into that silent sea—gliding along amid the eternal ice of the arctic circle. They proved of great service in breaking through the ice, dashing stem on against the massy barriers; then backing astern, to gain headway, and repeating the manœuvre until a passage was forced. When the ice was too thick to be broken in this manner, a hole was drilled in it, into which a powder-cylinder was placed, the mine fired, and the fragments dragged out by the steamers. The "Prince Albert" and "Felix" were taken in tow, for some three hundred miles by the steamers. Mr. Snow gives the following sketch and description of

[Pg 595] "I have before made mention of the remarkable stillness which may be observed at midnight in these regions; but not until now did it come upon me with such force, and in such a singular manner. I can not attempt to describe the mingled sensations I experienced, of constant surprise and amazement at the extraordinary occurrence then taking place in the waters I was gazing upon, and of renewed hope, mellowed into a quiet, holy, and reverential feeling of gratitude toward that mighty Being who, in this solemn silence, reigned alike supreme, as in the busy hour of noon when man is eager at his toil, or the custom of the civilized world gives to business active life and vigor. Save the distant humming noise of the engine working on board of the steamer towing us, there was no sound to be heard denoting the existence of any living thing, or of any animate matter. Yet there we were, perceptibly, nay, rapidly, gliding past the land and floes of ice, as though some secret and mysterious power had been set to work to carry us swiftly away from those vexatious, harassing, and delaying portions of our voyage, in which we had already experienced so much trouble and perplexity. The leading vessels had passed all the parts where any further difficulty might have been apprehended, and this of course gave to us in the rear a sense of perfect security for the present. All hands, therefore, except the middle watch on deck, were below in our respective vessels; and, as I looked forward ahead of us, and beheld the long line of masts and rigging that rose up from each ship before me, without any sail set, or any apparent motion to propel such masses onward, and without a single human voice to be heard around, it did seem something wonderful and amazing! And yet, it was a noble sight: six vessels were casting their long shadows across the smooth surface of the passing floes of ice, as the sun, with mellowed light, and gentler, but still beautiful lustre, was soaring through the polar sky, at the back of Melville's Cape. Ay, in truth it was a noble sight; and well could I look upward to the streaming pendant of my own dear country that hung listlessly from the mast-head of the 'Assistance,' and feel the highest satisfaction in my breast that I, too, was one of her children, and could boast myself of being born on her own free soil, under her own revered and idolized flag. But even as I beheld that listless symbol of my country's name, pendant from the lofty truck, my glance was directed higher; and as it caught the pale blue firmament of heaven, still in this midnight hour divested of star or moon that shine by night, and brightened by the sun; my heart breathed a prayer that He, who dwells far beyond the ken of mortal eye, would deign to grant that the attempt now making should not be made in vain, but that those whom we were now on our way to seek might be found and restored to their home and sorrowing friends; and that, until then, full support and strength might be afforded them."